They look up in the sky…

When Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 slammed into Jupiter, it was not a surprise. After first spotting the unusual, fragmented comet in orbit around the fifth planet a year prior, astronomers successfully calculated that it would make impact sometime in July of 1994. As a result, everyone was watching, not just through telescopes on the surface of Earth, but in outer space as well, where the Galileo, Ulysses, and Voyager 2 spacecraft each aimed their cameras at Jupiter to catch this never-before-seen cosmic event.

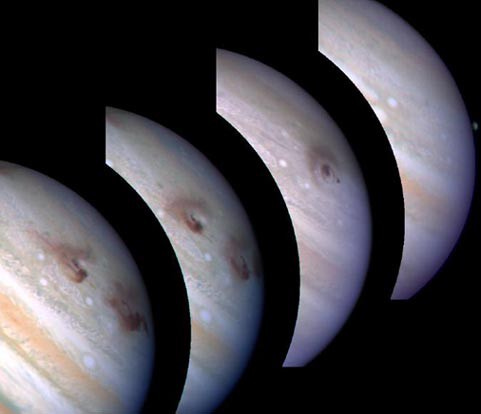

The first strike occurred at 5:13 eastern U.S. time on July 16th. For observers on the ground, the impact was experienced indirectly, as the first fragment of the comet crashed to the surface out of view on the dark side of Jupiter. Only later, when the planet had revolved to face the Earth, was the evidence of the event revealed through enormous spots of damage — as wide across as the Earth’s radius and more visible than Jupiter’s famous Great Red Spot.

The Shoemaker-Levy 9 impact continued for a full week, with 21 fragments striking Jupiter over that time. The largest impact was estimated to produce an explosion equivalent to 6 million megatons of TNT, and the massive craters were visible for several months following the event, dark blemishes on the marbled surface of the gas giant.

It was the first time that scientists were able to watch and study the live collision of two solar system objects. The event’s legacy was a better understanding of the protective role Jupiter plays for other planets in the solar system, with its powerful gravity capturing comets, asteroids, and other celestial bodies that might otherwise collide with Earth, producing more frequent extinction-level events. This phenomenon gave Jupiter a new nickname among astronomers: “The Cosmic Vacuum Cleaner.”

They don’t know what is going on, but something is out of line

On March 24, 1993, the night that the Shoemakers and Levy first spotted the ninth, and most famous, comet that would bear their name, Phish was playing the Luther Burbank Center for the Arts in Santa Rosa, California, a 1600-seat theater in Sonoma County. It’s hard to imagine a more stock setlist for the early 90s: A songy first set, a trio of tried-and-true jam vehicles in the second, a Big Ball Jam and a Fish segment, a Zeppelin encore. The two unique aspects are both pretty minute: it’s the rare show with two non-consecutive a capella numbers, and it’s apparently the point where even Fishman decided “The Prison Joke” was too tasteless to tell in public.

If you were trying to predict the future trajectory of Phish, you’d have to squint pretty hard at this show. There aren’t any unusual segues, the Melt, Tweezer, and YEM jams are all solidly median for the era, there’s an absurd 15 minutes devoted to Fish’s late-show hijinks — and a trombone solo from him in the first frame as well. Like so many shows far away from their New England nucleus, the setlist provides a Vegas buffet of genres, casting a broad net to try to win over as many new fans as possible.

Taking a big step back also doesn’t help much to judge where Phish was headed in early 1993. At this time, they were less of the singular force that they grew into later in the decade, instead battling in a friendly competition on the undercard below the stadium-hopping nostalgia roadshow of the Grateful Dead. Of their peers at the time — Dave Matthews Band, Blues Traveler, Widespread Panic, Aquarium Rescue Unit — it was anybody’s guess who would rise to the top of the heap when the Dead expired.

Someone particularly astute, observing the success of the early HORDE tours, could have probably predicted that 1994 was going to be a breakthrough year for this scene. But of all these bands, an oddsmaker would probably have placed Phish as the longshot to endure and succeed, based primarily on their prog-dork weirdness and radio unfriendliness. And by the objective measure of record sales, they’d be proven right.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. In 1993, the primary Phish objective was still to build the fanbase, and the best way to do that was to make their show a Good Time For All. Hence the genre shotgun approach to setlist selection, the audience participation gags like Big Ball Jam, silly dances, trampolines, vacuums and trombones, a capella songs, crowd-pleasing covers. It may have helped, but you didn’t need to have a deep tape collection to “get” what Phish were doing at the time, just a sense of humor and a tolerance for long songs and goofball lyrics.

So the most prophetic event of 3/24/93 may be the brief moment where Phish breaks from the image of friendly touring jamband providing shiny, happy tunes to dance and take drugs to. It comes in an unexpected place, just as the Shoemakers and Levy were looking for near-Earth objects when they discovered Jupiter’s orbiting comet.

As I said before, this night’s You Enjoy Myself is nothing special, moving in slightly sloppy fashion through its complex composition into a slightly stiff funk jam and finishing off with the four-man beatbox of a vocal jam, featuring bonus “Under Pressure” teases. But this latter section turns out to be unusually long, almost 8 minutes, and it grows progressively darker, eventually turning into hellish screaming and barely-audible Suspiria whispers until the band unifies in yelling “SHUT UP…NOW!” at its audience for reasons unknown.

Suffice to say, this is not your typical hippie-dippie, tie-dye, flower-power good vibes. And if it predicts the future of Phish in any way, it’s to foreshadow their increasing engagement with the uncomfortable, the confrontational, the downright evil. For all that Phish rightly deserves their characterization as one of the few bands that can pull off musical humor without sinking into novelty act status, it was only when they embraced the darkness that they started to separate themselves from the jamband pack. And 3/24/93 offers a glimpse of the impact that decision will make, in summer 94 and beyond.

AND IT’S HAPPENING RIGHT NOW

Roughly two hours after the first Shoemaker-Levy 9 fragment struck Jupiter, Phish walked onstage for the last show of their 3–½ month spring/summer tour. Playing at the base of a mountain at the Sugarbush Ski Resort, the band brought their trek full circle, starting, as they did on 4/4/94 in Burlington, with the one-line a capella stinger of “Back in My Hometown.” Despite a ho-hum first set, they went on to play a show that was a staple of 90s tape collections, one considered monumental enough by the band to be issued as Volume 2 in their LivePhish CD series.

Funny then, that the middle of the second set’s opening Run Like an Antelope contains one of the most awkward on-stage moments in Phish history. Reciting the arcane incantation of Catapult, Trey chuckles before the line “There ain’t going to be no wedding,” a Freudian accident in the last show before Anastasio’s nuptials. Never one for subtlety, Fish offers up the counterpoint “No wedding? You wish!” and Trey’s reply is aptly described by Scott Bernstein as “If a chord could kill, the one Trey plays after Fish says that could kill.” Quickly, cringingly, Fish apologizes, and the band re-enters Antelope for five savage minutes of Trey’s noisy new ’94 style, not so much playing his guitar as torturing it while the band hits a rabid, deranged sprint.

Those evil spirits aren’t easily shoved back in their box, haunting the closing Rocco section — Mike’s intense two-note bassline, Trey’s gusts of feedback and megaphone sirens, Fish’s pinched screams all return at various times. Even the Simpsons tease is of Treehouse of Terror variety, with someone (Trey?) letting out a cry of pain instead of the customary “Doh!” From start to finish, it’s about 19 minutes of white-knuckle thrills, a horror show in the middle of their warm and fuzzy home state reunion. Not coincidentally, it’s arguably the best Antelope they’d ever played to that point, it’s only competition the 8/14/93 seguefest, a much less-focused, lighter-spirited affair.

Even if the rest of the set doesn’t come close to revisiting that intensity, its effects linger. Since its earliest days, Phish was no stranger to the dynamics of tension and release, constructing many jams (most frequently, Stash) that perseverate on dissonant patterns for several minutes before triumphantly resolving. But while those jams skillfully built a musicological tension/release, it wasn’t until the mid-90s that they discovered the power of an emotional, overarching, thematic tension/release, a game of contrast that could be played over the course of an entire set or show, instead of just within a single jam. Here, the frothing lunacy of the set-opening Antelope brings later moments into sharper relief, be it the playfulness of the comet-themed Harpua or the delicate glory of a typically great ’94 Harry Hood.

This approach didn’t suddenly come to life on 7/16/94 — this whole comet metaphor doesn’t fit that perfectly. There are numerous previews of these rumblings in the spring/summer of 1994, from Trey’s new effects pedals that allow him to expand beyond his crystalline primary tone, to the anachronistic deep sea exploration of the Bomb Factory and the crazed seguefests of June. There’s a slow, barely perceptible shift from the polite Vermonters trying to win over new fans by showing off everything they can do, to the mischievous pranksters (the kind that would, say, steal cadaver parts and send them to friends) who aren’t necessarily on the same team as the audience at all times.

An interesting question to ponder is whether Phish evolves at a faster rate while on tour, or between tours. While we can hear what happens over a run of shows and try to observe and analyze any progression that playing together almost nightly produces, the time between tours is a black box where we have no window on the decisions being made. My hunch is that in the modern era the changes within a tour outpace those between tours, since the band largely goes their separate ways when not on the road. But the difference between 4/4/94 and 7/16/94 is not so dramatic — particularly when compared to the first set of 7/16 — while the fall of 1994 represents probably the biggest step forward in the band’s career to date.

Did they take the violence of the 7/16/94 Antelope back to the lab for the three months between summer and fall tour and craft a new, more challenging, yet more deeply rewarding live strategy? Was it the first strike of many, leaving deep scars on the dark side of Phish that wouldn’t fully reveal themselves until the next rotation, deep impacts that would remain visible for months, if not years? Like Jupiter’s role as the “cosmic vacuum cleaner,” would Phish soak up further impacts in the coming years that would alter their landscape, while remaining firm as the largest body in their particular solar system? There’s only one way to find out: keep your telescopes pointed at the sky.