SET 1: The Old Home Place, Punch You in the Eye, Reba > Cars Trucks Buses, The Lizards, Sample in a Jar, Taste, Fee -> Maze, Suzy Greenberg

SET 2: The Curtain > Runaway Jim, It's Ice > Brother, Fluffhead, Run Like an Antelope > Golgi Apparatus > Slave to the Traffic Light

SET 3: Wilson > Frankenstein, Scent of a Mule, Tweezer, A Day in the Life, Possum > Tweezer Reprise

ENCORE: Harpua

In 1994, Phish released their first, and only, music video to MTV. Directed by Mike, the Down with Disease video showed the band members goofing around in scuba suits with the aquarium stage props, as well as band iconography such as the vacuum, the megaphone, and Marley, then finished with live footage from 12/31/93. It aired, according to Wikipedia, “a few times.” It was most commonly seen as a subject of mockery on Beavis & Butthead (though in fairness, the duo are mostly mocking fish, the animal).

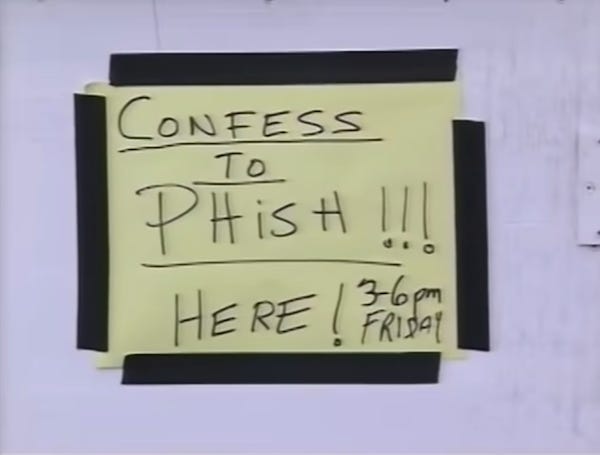

A couple years later, the same day that Phish played the Diseezer in Seattle, MTV dedicated a full half hour of Wednesday evening airtime to the band, screening The Clifford Ball: A Beacon of Light, a documentary short directed by Vicky Bippart. The 28-minute film shows the operational prep, the traffic, Ball Square, Mike talking to fans on a golf cart, the Flatbed Jam, the orchestra set, and the mayor of Plattsburgh walking around the lot. But most importantly, it contains long segments of The Curtain, Fluffhead, Brother, and Reba from the festival, the purest Phish delivered straight into American homes after school on a Wednesday.

Yesterday, I got my Grinchiness about the music at The Clifford Ball out of my system, and I thank you all for not biting my head off. Today we talk about the considerable non-musical importance of The Clifford Ball, an event that gave Phish and their fans something they long craved, even if they wouldn’t quite admit it: mainstream legitimacy. It’s not a cool thing to lust after, if you’re an artist, but it certainly doesn’t hurt your bottom line, and only the strongest-willed creative people are able to function without some form of external affirmation. Phish may be one of the most successful cult bands of all time, but they also signed to Elektra, made a blatant crossover attempt with Hoist (not to mention a music video), and watched a number of their jamband scene peers surge up the charts while they toiled in relative obscurity. They weren’t saying no to becoming a household name.

But they accomplished that reluctant goal in the most genuine way possible: simply by building the largest American festival of 1996, and playing it by their own damn selves. For all the credit Phish deservedly gets for giving birth to the modern American music festival, the most audacious aspect of The Clifford Ball and subsequent Phish festivals is that they were the only act: no second stage (Oswego aside), no opening bands, and no guest appearances (except for 10 seconds of Ben & Jerry). Two years earlier and three hours down I-87, Woodstock 94 had drawn 350,000 people with dozens of the decade’s most popular artists and an invaluable rock and roll brand. The Clifford Ball drew about 20 percent of that, with a solitary band that most of the world still hadn’t heard of.

I imagine that even Phish were shocked at the size of The Clifford Ball. It’s a pet theory of mine that Phish possesses a small fraction of the fanbase of their peers on the shed-and-arena circuit, given that so many of their customers repeat from show to show. Even selling out Madison Square Garden at the time must have felt a little smaller when you see the same faces night after night in the front row (such as the fan Trey shouts out on 8/17, none other than the intrepid @neddyo). But successfully luring an NFL-size crowd to a fairly remote location to camp out for two or three days in the August heat, just to see you — after that, you can’t pretend you’re in Nectar’s any more.

The same feeling goes for the fans too, if not even stronger. The Phish fans that patiently sat through hours of traffic and security checkpoints to get into the festival had mostly seen them at much smaller venues and spent time listening to tapes at home, maybe knowing a few IRL friends that liked the band or finding a slightly larger online community to nerd out with. But Phish was still everyone’s little secret, a band that was passed on by word of mouth at Jewish summer camp or guitar lessons or in tape-trading forums. Driving through the tall statues at the gates of Plattsburgh AFB under a banner reading “Prepare for Flight,” then seeing line after line of cars, tents, and people, all of them there to see their favorite band too; I mean, it must have been heaven?

And that’s before you even get into the amount of time and care that Phish Inc. put into the experience for festival attendees, inspired by immersive events from Vermont’s Bread & Puppet Theater. From what is shown in the documentary, The Clifford Ball was charmingly DIY compared to later Phish festivals: Ball Square is a smattering of plywood buildings, and the extracurricular entertainment (stunt planes, trampoline dancers, dudes on stilts) was cool but a bit conceptually loose. Still, compared to the concerts and festivals of the time (and especially today), where every attraction is designed to milk you of your money and data, it was a delightfully immersive environment, long before that would become code for ‘gram-worthy. “Our intent is all for your delight,” as future Phish festivals would say.

Between the size, the spectacle, and the successful logistics, the world couldn’t ignore what was happening in Plattsburgh. The local news showed up, Rolling Stone begrudgingly blurbed, and a few months later, MTV gave in, lest they miss out on a rising strain of youth culture. The airing of the Clifford Ball documentary, practically an infomercial for Phish, is up there with A Live One in converting new fans to the Phish cause — even watching it now makes me want to hop on tour immediately. Until The Clifford Ball, Phish was proudly under-the-radar. Now they were definitely on it, and no longer a “small band” by anyone’s objective standard. What to do next?