It may feel like ancient history, but we are still in the same calendar year as the release of Phish’s most recent studio album, Hoist. As is typical for Phish, any pretenses of promoting that album have fallen by the wayside; shows this fall typically feature 2 or 3 Hoist songs, no more representation than its predecessors receive. Some songs are now regular rotators — you can count on hearing Sample, Disease, and Mule every couple shows. Others are nearly forgotten, including Demand and (weirdly) Wolfman’s, both of which haven’t been heard from since June and won’t be again until next fall.

But even for the Hoist songs that have integrated smoothly into the Phish catalog, it’s notable how little they’ve evolved over the heavy touring year of 1994. Unusually, Hoist was full of songs that hadn’t been workshopped live — only Sample, Lifeboy, and the original-lyrics Axilla debuted before its March 94 street date. So a lot of these songs were expected to grow to maturity after their studio version was locked in, a reversal of the usual Phish song pipeline.

But perhaps for this very reason, a lot of the Hoist material stubbornly refused to stretch out over the course of 1994. We know that Sample and Axilla never really will bloom beyond their original state — jam-filled gimmicks aside — and If I Could, Lifeboy, and Dog Faced Boy, as ballads, were never really expected to. Scent of a Mule would eventually pick up its signature (and divisive) mid-song Trey/Page duel, but for now it’s basically just a piano solo before the klezmer kicks in. After a handful of awkward appearances, Wolfman’s Brother was basically shelved until a future version of the band more comfortable with slowing down could tinker with its groove potential.

So it was up to the first two songs of Hoist to make the biggest strides in 1994. Julius and Down With Disease both immediately entered the rotation and have never really left; Disease was even preemptively inducted with its partial appearance at 12/31/93. And by mid-fall, both sound significantly different from their April introduction, and even more so from their studio versions. On this night, the beginning of Fall 94’s second leg, both appear in performances that encapsulate their year-long metamorphosis and point to what Phish itself would become in the next year.

Julius, on Hoist, was a real stretch for Phish. You could tell just from the liner notes — no Phish song had ever boasted a cast list this long, with both a chorale and the Tower of Power horns credited. Musically, it aims for a gospel-blues strain far more earnest than anything they’d attempted before. Don’t get me wrong, I love me some Phish jazz, but Magilla and The Landlady — or early versions of Gumbo, for a more one-to-one comparison — sound way more stiff than the New Orleans-style swing of Julius...at least on Hoist.

From the start, that vibe proved much harder to recreate on stage. The debut of Julius, and a couple other versions in Spring 94, have the Giant/Cosmic Country Horns on board to help, and the band makes a game, pretty adorable effort to recreate the rave-up gospel choir outro for a while. But pretty quickly, the band speeds up the tempo and sands off the swing, transforming Julius into straightforward blues-rock, more ZZ Top than Professor Longhair.

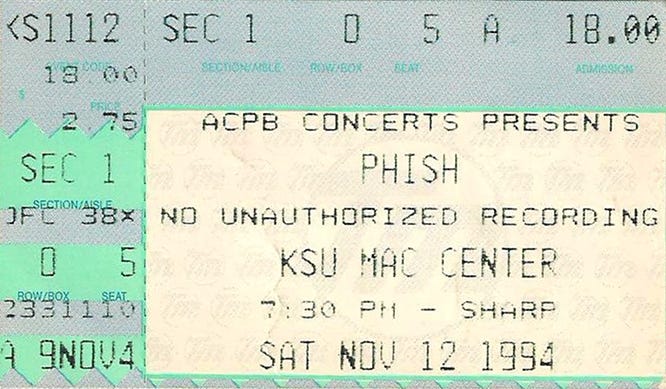

The song progresses incrementally in this direction until you arrive at what you have on 11/12 at Kent State University: a full-fledged arena-rocker. Instead of the sort-of stodgy throwback it is on the album, it’s now a high-adrenaline second-set opener, with a good four minutes of Trey soloing and Fishman’s once-supple groove juiced up to bashing the cymbals like a caveman and hooting along. You can probably tell it’s not my favorite kind of Phish, but it certainly suits the environment; perhaps if they had stayed in theaters, Julius could’ve grown in more interesting directions, but in this timeline it’s ideal material for Phish’s new arena-rock phase.

Then there’s Disease, which was literally born into the arena world, its mammoth riff having debuted at the climax of one of Phish’s largest shows to date, NYE 93 in the Worcester Centrum. Disease didn’t need to change at all to effectively fill the big rooms Phish was now playing; it’s got a punchy intro, a catchy chorus, and that triumphant ending. It could have stayed like Sample, with a little more room at the end to stretch out the solo and play variations on the finale riff. And that’s mostly what it did...until this show.

After 52 versions, 11/12/94 blesses us with the first deeply improvisational version of Disease, and right away, it’s a keeper. It’s business as usual for 6-1/2 minutes, but Trey’s solo is testing the song’s structure for flaws, slowly eroding the jam’s typical rhythmic structure. When it fully diverges at 6:40, you expect it to snap back to normal any second, but instead, the spirit of the Bangor Tweezer slides into the room, and we’re off into the disorienting stop-start jamming that is a hallmark of Fall 1994’s deeper moments.

The jam builds tension with unforgiving (and undanceable) intensity, but instead of releasing back to Disease, it disintegrates completely into a very dubby version of Have Mercy. After that reggae diversion is another breakthrough, as they find a novel use for that big Disease riff: a life preserver for when the improvisational waters have gotten too treacherous, and the band needs to maneuver back, ASAP, to pure rock and roll. It’s the first Disease-prise, and it rules, creating an arena-rock sandwich with some truly experimental music in between.

Between Julius and Disease on 11/12/94, you get an accurate picture of what Phish is going to sound like for the rest of the 90s: a band that can rock your face off one moment and make you stroke your chin the next. Julius demonstrates how more subtle items in the Phish songbook could be retrofitted for arena stages, Disease shows that they’re not content with merely stopping there. As the venues get larger and the sound gets bigger, it just provides a broader platform from which to take even riskier leaps.

[Stub from Golgi Project.]