Down, Down, Down

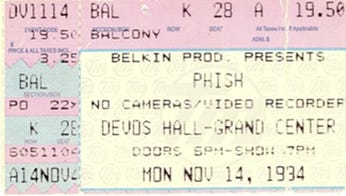

11/14/94, DeVos Hall, Grand Rapids, MI

In doing some research, I stumbled upon an interview by the great Steve Silberman with Trey from the end of this tour, helpfully reposted by Jambase last year. It’s a goldmine — you’ll probably be seeing it a lot here in the next month — because Trey is surprisingly candid about the tour they just played and how they hope to capture it on next year’s A Live One. For today’s post about the show at DeVos (ugh) Hall, one segment jumped out at me:

TA: Songs have a will of their own. Two or three years ago, we were never playing “Split Open And Melt.” It just was off the songlist. “How come you guys never play ‘Split Open and Melt?’” But it just wasn’t in us. Then all of a sudden, it started to get good. At the end of two tours ago, we played the ultimate “Split Open And Melt” jam, and we put one of them on Hoist. We just discovered how to play it, because it’s got this really weird time-change that was throwing us off. But that one at the end of Hoist was the first time it clicked. “Split Open And Melt” went from being a big pain in our butt to – this is how you play “Split Open And Melt.” For the next year, it was incredible. We played one at Red Rocks.

SS: That whole tape is unbelievable.

TA: You know what I mean about that “Split Open And Melt” – it was just screaming. Red Rocks was the night that it broke through. We have it on multitrack. But the one at Red Rocks was the end of the cycle. It peaked, and never got as good as that again. This tour, it didn’t have it anymore – the magic. It’s weird. Now “Split Open And Melt” is back on the back burner again.

I love when members of the band cite specific performances that they enjoyed, but I’m even more interested when they mention one that they weren’t happy with; for a recent example, I’m fascinated by Mike’s ambivalence towards the “jam-filled” night of the Baker’s Dozen. Trey throwing an entire song under the bus, at least for this specific tour, is really intriguing, even more so given that it’s Melt, one of my favorite Phish songs to analyze.

Melt is a wild beast, and certain eras of Phish have struggled to tame it. It has a wider floor-to-ceiling range than most Phish jam vehicles, which, for all but the sloppiest eras, are competent and well-played at worst. Conversely, Melt, with its unusual rhythmic meter, has the highest chance of going completely wrong if the band is not at its sharpest and most communicative. In 3.0, it’s especially high-risk, high-reward, as the band has often struggled to stay tethered to its backbone while still exploring its potential for deep, dark jamming.

As Trey mentions, Melt clicked for the band in 1993, so much so that they stuck the 4/21/93 jam at the end of Hoist. But that was a different kind of success, one where they still stayed mostly rooted in the jam’s twisty structure, only occasionally breaking free for short “look ma, no hands” periods. That was good enough for 1993 Phish, but 1994 Phish is more ambitious. Expertly navigating a jam’s standard parameters, even when those rules are more complex than the usual slow build, is so last year.

I actually have enjoyed a lot of 1994 Melts; I’d never be as harsh as Trey is in this interview. But I can kind of see why it’s frustrating to him at this particular moment. This night’s version does seem pretty clumsy — it’s noisy and brisk, but doesn’t ever break free of its chains, and Trey wraps up the jam early and abruptly, barely making it over the ten-minute mark. It’s possible that at this point in the band’s development, the intricate structure of the Melt jam is too on-rails, when Phish is itching to explore a more open world.

So what is working for them? Let’s go back to Trey:

This was the tour for “Tweezer.” My guess is that “Tweezer” is going to be on the live album, because we were doing things with it that we’d never done before. You can’t predict it. It’s just all these cycles. I remember when “Runaway Jim” was pushing all kinds of boundaries. I don’t know why that happens.

There’s no Tweezer in this show, but there is an absolutely massive, relentless, fantastic David Bowie clocking in at over 26 minutes. Bowie also had an amazing tour, enough so that I often Mandela Effect myself into thinking it’s on A Live One. If Bowie actually had made the cut, this would make a suitable substitute for the Bangor Tweezer, as it’s far more focused — though also far more malicious.

Tension/release jams might be the oldest Phish trick in the book, but this Bowie takes it to a ridiculous extreme. Once the Bowie jam kicks off, there’s a ceaseless 9 minutes of atonal aggression, with the band trading various shards of anti-melodies and rolling the volume knob back and forth. In the 14th minute, the tension finally breaks...for 30 seconds, then it snaps right back to terror, eventually dropping out to silence so that the crowd can (spontaneously? Or following band instructions?) conduct a satanic ritual of solemn woos and claps. It’s a dress rehearsal for 12/29’s legendary haunted-house version, complete with a segment of creepy whistling before finally raging its way back into the sunlight.

What Tweezer and Bowie share is a much less fussy jam structure. Tweezer is barely a song at all, it’s just a riff that spills out into funky territory, loosely pointed at a dying-battery ending that was easily jettisoned when it proved no longer necessary. Bowie has much more going on before and after the jam, but the improvisational lines between are faintly drawn, little more than a starting key, a preference for the hi-hat, and an ultimate destination that lets Trey go The Full Van Halen.

These types of jam spaces, more ellipsis than mathematical equation, are the new fertile ground for Phish. Melt would eventually get back in with the cool crowd, once Phish figured out how to use its deranged meter as a springboard instead of a cage, but for now it’s in retrograde. The big Type II jams of Fall 1994 may be dense, busy, and a little bit stiff, but when it comes to the songs that most reliably launch them, less is definitely more.

[Stub from Golgi Project]