“You know what helps me? Doing two-nighters. Hanging out with people after the first show in San Diego wrote the songlist for me – people saying, ‘Hey, you haven’t played this in a while.’ I really felt that I knew who was in the audience, and what they were going through. I had been on the same street that they had been hanging out on all day, going to the same bars the night before. So we’ve been talking to our booking agent, and next tour, we want to do a lot of two-nighters almost everywhere.”

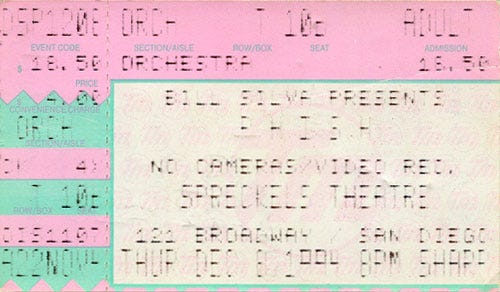

That’s Trey talking to Steve Silberman at the end of the Fall 94 tour, after they had performed a rare-for-the-time multi-night stand at the tiny Spreckels Theatre in San Diego. In this case, staying overnight very much seemed like a business decision instead of an artistic one; at 1360 capacity, they needed 2x the shows to meet their usual ticket quota for a tour stop. But Trey’s takeaway from the doubleheader, that there was a richer story to be told if the band stayed stationary, would foreshadow much of the band’s future — including precisely 25 years later, when they’d be finishing up a 3-day weekend in Charleston.

Two-night stands weren’t totally unheard of before San Diego in 1994 — most recently, they played back-to-back shows at Great Woods and Red Rocks in the summer, and there were three-night stands at the Beacon and the Warfield in the spring. And it’s not like Trey’s conversations with fans led to a totally outlandish setlist on the second night at the Spreckels; there are only moderate, acronym-y bustouts of PYITE, MMGAMOIO, and WMGGW. But the band sounds fresh as heck after not spending the night on a moving bus, turning in a much better show than they did on the previous evening.

As I wrote about the Great Woods run, having four sets to fill up instead of two allowed Phish to assemble a longer narrative, something that would have appealed to Trey in his more calculated setlist-crafting days. In Mansfield, they took that storytelling potential literally — the first set of 7/8 was a Gamehendge, which combined with the no-repeats policy (for only two shows? Pshaw.) to knock the band out of their usual setlist habits. The result was the accidental creation of the modern Phish approach to the two-set format, with 7/9 partitioned into a songier first set and a jammier second set.

Five months later, the jammier side of Phish is way more developed, and the luxury of a two-night run in late Fall would seem to be the ideal place to revive one of those half-hour voyages they tinkered with in November. That doesn’t happen, for whatever reason. Instead, the entirety of 12/8 operates like the second set to 12/7’s pervasive first-settiness, an advanced-level course after the previous night’s Intro to Phish.

For starters, there’s an unusual Makisupa opener, “reportedly a commentary on some issues between fans and police around the venue,” according to Kevin Shapiro’s show notes. [Sidebar: I can’t find much information on whatever happened outside the venue that day, though Silberman mentions talking to fans who were “roughed up by the police” in his interview with Trey. If nothing else, it was a reprise of the crowd issues experienced earlier in the tour on the other coast, further evidence that the scene was getting too unruly for the campus-and-theatre circuit, even 3000 miles from their home turf.] Later in the first set there’s the welcome return of Punch You In The Eye, a short but serious Simple > Catapult > Simple, and the first While My Guitar Gently Weeps since the show after Halloween.

The second set doesn’t go for one big jam, but spreads out the improv generously. There’s not a single show-defining moment, but Possum and Reba both get a luxuriously long run-through, each taking advantage of the intimate venue and attentive crowd for Trey’s latest favorite trick: the quiet jam. On the 7th, you’ll hear maybe the last Divided Sky pause with a completely silent audience during the pause, and that clearly inspired Trey to go back to that well for the second night. The Possum, especially, stays barely audible for a perversely long period of time, an extension of what Trey told Silberman he’d been trying to do in Foam.

“It’s a really intense moment, because people are hearing it get quieter and quieter, and they’re following the way the music is going, and there’s a line somewhere – for each person, it’s probably a little bit different – where it gets quieter than the threshold of their ability to hear it. But I’m sure people are still hearing it, even after it crosses the threshold. For me it’s like, “Are they still hearing what I’m playing in my mind, or are they making it up?” Because if they are making it up, then that’s the greatest thing of all, because you’ve got a really creative audience going.”

I’m not sure how many fans would have been repeat customers at this point, given the band’s limited penetrance into California and the midweek scheduling. But anyone who did attend both nights got two very different experiences; maybe not a cohesive story, but a two-episode anthology that gave Phish the space and confidence to gain back some of the experimentation they’d shelved over the last week in California.

“You definitely get a vibe from the crowd. They react when we take risks and go someplace we’ve never been before. You sense that. And you read the mail and phish.net. You know that people are coming to a lot of different shows, so you don’t play the hit song every night.

The audience made that situation, as well as us. It’s what we’re happiest doing, so we try as hard as we can to move it in that direction – to be in a situation every night where everybody is hoping for spontaneity. The people who like that kind of thing enjoy the concert, and come again, so eventually, there are more and more people who want to hear risk.”

[Stub from Golgi Project]