SET 1: 1999 > Mike's Song > I Am Hydrogen > Weekapaug Groove, Ghost -> Ha Ha Ha > Cavern

SET 2: NICU > Character Zero > Tweezer -> Cities > Wading in the Velvet Sea, Run Like an Antelope > Frankenstein

SET 3: Runaway Jim -> Auld Lang Syne -> Simple, Harry Hood > Tweezer Reprise, Llama

ENCORE: While My Guitar Gently Weeps

Lion in My Pocket

New Year’s Day is a time for resolutions, New Year’s Eve is a time for apologies. I know I ruffled a lot of feathers by calling 1998 “the best calendar year the band would ever play,” because every time I gave a show this year a less-than-gushing review, I got a bunch of comments asking if I was going to revoke that claim. Well, you did it, you finally wore me down, and I’d like to revise my statement in two ways. For one, I should have said that 1998 is my favorite year of Phish, a subjective assertion that survived a year of close analysis. And secondly, I’ll edit myself to say that 1998 isn’t the best year of Phish…it’s merely the Most Phish year of Phish.

To explain, I’ll dig up a term that shows up occasionally in arts criticism: “imperial phase.” It’s a description I learned from one of this essay project’s most direct inspirations, Elizabeth Sandifer’s Doctor Who blog TARDIS Eruditorum, which often applied it to the David Tennant/Russell Davies era of immense critical and popular success. But as Tom Ewing wrote in a 2010 column on Pitchfork, it originated with another Tennant – the Pet Shop Boys’ Neil, who self-applied it to describe his pop group’s commercial and artistic peak.

Ewing writes, “you need three things for an imperial phase: command, permission, and self-definition.” It’s the point where an artist’s creative vision and years of hard work suddenly connect with popular approval, with combustible results. The artist, brimming with confidence, can seemingly do no wrong; their audience is expanding and uncritically adoring, showering attention and dollars. Today’s obvious imperial phase example is Taylor Swift, before her it was Beyoncé, Ewing writes about Lady Gaga, Madonna, and – germane to today’s show – Prince.

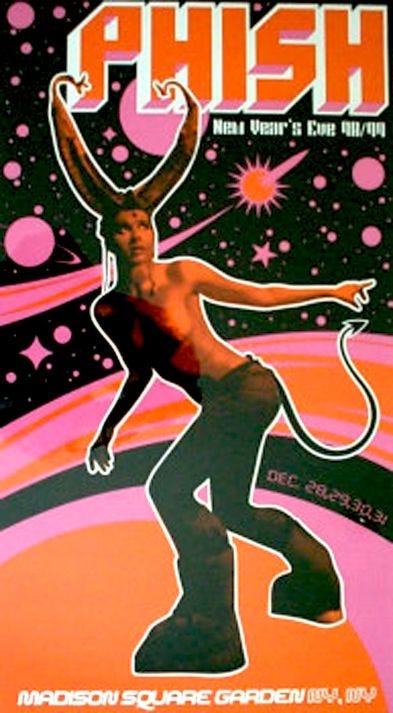

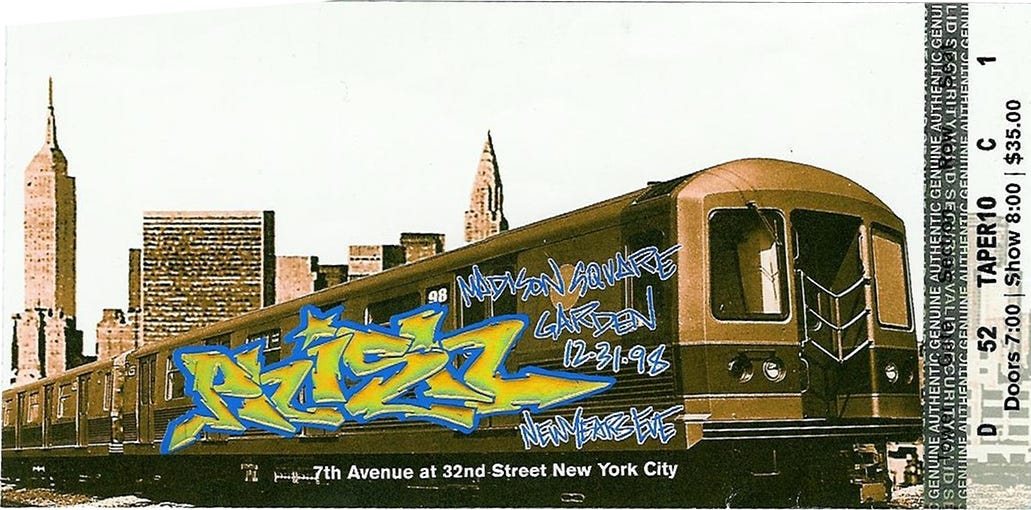

It’s sort of absurd to put Phish in this company, as Ewing is talking about massive pop culture success of the sort that our boys never even sniffed. But within their own bubble, I think it’s accurate to call 1998 – or perhaps late 1997 through Big Cypress – Phish’s imperial phase. There’s command in the post-1997 swagger I have spent many an essay this year describing, and permission in the band’s effortless ability to sell out practically any venue they want from coast to coast, from northern Maine airfields to Vegas arenas to Madison Square Garden for four consecutive nights. But most importantly, there’s self-definition – this is the final era of Phish that the band will forever be compared against.

All of the ingredients I described back in April contribute to this iconic status. There’s the structural details: the European tour, the full summer and fall itineraries, the summer festival and the Halloween costume. Then there’s the new album and its accompanying promotional machinery, plus the invitations to play with Neil Young and a slew of other notable names, drawing them into an industry mainstream they’d largely skirted. And of course, there’s the music, expanding upon the innovations of 1997 but still attentive to the details of their early material, while also stretching the catalog with a bounty of interesting new covers and original compositions. The band and its audience never had it so good, and never would again.

Life is Just a Party

All of these imperial qualities are on full display for the year’s final show. Hell, they’re all present in the first six songs, a 55-minute suite that Phish delivers in calm conqueror mode on their highest-pressure night. There’s the self-assurance to play the obvious cover as the opener, knowing that the crowd is going to pop as hard as the walls of MSG have ever heard at the titular line. They maintain the momentum by diving immediately into a classic-style Mike’s Groove, which flaunts the band’s control of the room by cooling off nine minutes into Mike’s Song for a mellow and gorgeous segment that soothes the delirious crowd.

After a Prince-haunted Weekapaug cranks the energy back up, the band absolutely luxuriates in Ghost, a masterful version where idea after idea laps up on shore. Check out how Trey develops that first melodic theme of the jam in real time, figuring out the front half at 5:23, trying out a stunted tail at 5:38, pausing to regather, and then revealing the whole thing, fully composed, at 6:00. Less than a minute from conception to reality, absolute magic.

Like the 11/9 Gin, but much less irritating, it’s a melody that haunts the whole jam, mostly invisibly – you can hum it over any of the next several minutes. But the band stays in forward motion, arriving at a thrilling motorik groove for the final segment. When it blasts into Ha Ha Ha, they’re not celebrating a well-executed prank, but cackling about their complete and utter dominance.

The rest of the show loses some of that firm command, but still distributes intriguing islands everywhere. In the second set, both Tweezer and Antelope work themselves into unusually introspective corners, despite the ramping intensity as midnight approaches. The band climbs right on that bucking bronco for the pre-countdown Jim, turning the constraint of jamming along to the clock into a feverish inspiration.

And after midnight, both Simple and Hood (a 7-½ minute intro!) return to that dreamy mood, pushing back against the crossfire percussion of popping balloons and glowring smacks. Just under the wire, they’ve found a balance between the two opposing poles of 1998, weaving together the ambient and the ambush.

Parties Weren’t Meant to Last

The problem with an imperial phase is that pesky second word; phases, by nature, are temporary. As Ewing wrote, “There's something double-edged about the concept: It holds a mix of world-conquering swagger and inevitable obsolescence. What do we know about emperors? That they end up naked: The phase always ends.” Later, referencing his chosen example of Lady Gaga, he identifies the terminal cause: “There's a will for her to go further, to get better each time, which must be intoxicating-- of course many imperial phases end in hubris.”

A year ago, I spied some early cracks in the Phish facade at the end of 1997’s breakthrough. But the band mostly held it together for 1998, with the escalating chaos in the crowd and the dressing room not yet affecting the four of them when they were playing. Tonight, there are signs that the protective force field of being onstage together is weakening, most significantly in how short these sets are – only one, the second, gets past an hour, and even there it’s by a whisker. After the opening suite, it feels like every other song is a set closer, with “oops, set too short, play another one” moments at the end of both II and III. The midnight gag – likely because of the scrapped concept for the entire run – is pretty phoned-in, basically just a balloon and glowring drop. As good as the music within gets, you feel a slight sense they’d rather be hanging with their buddies backstage instead of us.

But I find Ewing’s hypothesis more interesting than the usual “Behind the Music” second act. The band’s relentless drive to always evolve must have been exhausting, and only a year after 1997 rewrote the rules of Phish improvisation – a process that was at least two years in the making – they were at it again, pushing themselves to make weirder, spacier, more entropic music. I don’t recall a lot of backlash from the audience, as 1997 had already weeded out anyone who wanted Phish to stay in 1995, or 1993, or 1988 forever. But I think the strain of constant creative destruction and recomposition was starting to take its toll internally.

Five months after this show, Trey would return to the road for his first tour without his three usual companions, playing new material divorced (for now) from Phish. When the band properly returned at the end of June, their setup would be reshuffled for the first time since they squeezed horizontally onto the shallow stage at Nectar’s, with Trey off to the far right and Fishman moved back off the front line. Maybe the switch was just disorienting to fans, but it certainly felt like it came with a subtle but noticeable decline in band chemistry and body language, as Trey seemed increasingly isolated both musically and on stage left.

Along the way, the tension between quiet textures and loudness wars that started bubbling up in Fall 98 will only get sharper. I’m not sure who was on what side of those battle lines, and it’s probably simplistic to even think of it that way, but there will be more and more of the musical disconnects that seemingly triggered awkward moments like Halloween Set 3. While the year to come isn’t a disaster, it does start to feel like the band’s confidence is shakier and the triumphant recoveries less frequent.

Which leaves 1998 as the high water mark, Hunter S. Thompson’s place where the wave finally broke. Ewing wrote, “an imperial phase sustains a career but also freezes it: Empires decline and the memory of former glories dies hard.” So it’s doubly appropriate the final show of the year opened with “1999,” a song about coping with apocalyptic anxiety by partying hard that has aged into nostalgia for the misremembered innocence of the pre-9/11 world. Phish’s imperial phase was riding that current of millennial dread, scoring a party at the end of the world that couldn’t be sustained forever. But it will always look like a golden age from afar.

=====

Happy New Year everyone! Thanks for joining me on another trip around the calendar. As mentioned the other day, this newsletter may move shop before my next posts in four months or so (I haven’t quite decided yet how I’m going to handle Trey’s tour). If I switch platforms, I’ll make it as easy as possible to transfer subscriptions. In the meantime, enjoy your holiday, whether it’s in MSG or elsewhere, and your early 2024. See you soon, in 1999.

Thanks for another great year of newsletters Rob! Can't wait to read about the Gamehendge thing in 2048.

Your essays are always astute and engaging, and this one especially so. Thanks for all you do, and happy new year.

I love 1999 (the song is great, but I’m referring to the year), however, I can definitely see how it might have been a problematic year for the band even as they made some of their most intriguing music. Excited to see your take on it, wherever that may be hosted.