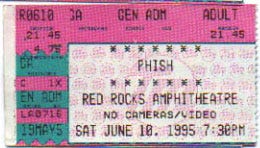

Now that’s more like it. 17 days before A Live One was released, Phish blessed Red Rocks with a massive improvisational sequence that already put the 1994 highlights on that record out-of-date. Through the vehicle of their oldest song suite, Mike’s Song > I Am Hydrogen > Weekapaug Groove, Phish assembles 36 minutes of dark, intense, multi-varied, narrative, experimental, and anthemic jamming that firmly establishes the tone for the rest of 1995, five shows in.

In my mental conception of 1995 Phish, the giants of the year are Mike’s and YEM, an impression no doubt biased by the legendary versions that await in December. So it’s fitting to hear the former provide the year’s first big highlight, in a performance that obliterated the song’s runtime record at just a click over 20 minutes (according to the jam chart, no prior version was longer than 13:17). But it’s even more heartening to hear both sides of the Hydrogen sandwich firing at the same time — typically in Phish history, either Mike’s or Weekapaug is ascendant, and the times when both peak simultaneously provide an eclipse that’s worth ritual celebration.

The full sequence is on Live Bait 6, if you have those mp3s or a LivePhish+ subscription handy. There’s even video evidence available, if you can handle the disorienting combination of strobe lights and VHS pixelation.

I’m honestly kinda gobsmacked by how fully-formed this jam arrives — this project is all about charting the incremental evolution of Phish, and here’s a sequence that predicts just about the entirety of the late 90s, with no real precedent. But we can at least start to crack it by backing up and looking at the earlier moments of this show, trying to tease out what led to such an abrupt breakthrough.

The first set is, charitably, sloppy fun. The Makisupa > Llama opener is a tempo-shift delight, but the following trio of Caspian, It’s Ice, and Free is wobbly as hell. A blistering Rift sets things a-right, and there’s a pretty excellent YEM that, strangely, initiates what feels like an end-of-show sequence in the first set: a Fish song (the last Lonesome Cowboy Bill until Phish plays the whole dang album) and a Suzy.

But here’s the subtext of this uneven set: Page absolutely kills it. As Ice stumbles in, he’s the only musician holding it down. On Free, Trey’s mini-kit experiment (which I will explore more deeply soon, I promise) gives him room to shine in a melodic leadership role. That vote of confidence pays off subsequently with Page co-lead moments in YEM and Suzy, not to mention his cheeky decision to drop “Fanfare for the Common Man” teases while Fish takes his sweet time setting up for his segment.

When they get to Mike’s in the middle of the second set, that dynamic is still in place. For the first 7:40, Mike’s rages as usual, and it flirts briefly with last year’s standard segue into Simple. But Trey resists that easy off-ramp — perhaps inspired by Kuroda’s psychotic, relentless strobe lighting — and instead drives down darker channels into territory that was largely reserved for the experimental Tweezers and Bowies of last fall.

But it’s startling how abstract Trey gets; by 12:00, he’s no longer playing notes, just swirls of ambient noise. The rest of the band comes to a halt — this spacey mode is still unfamiliar turf for them — and it feels like the doorbell notes of Hydrogen could come to the rescue at any moment. But who’s that contributing buzzing sweeps from his brand new synthesizer (first heard, I believe, on the 6/7 Ha Ha Ha)? And whose modal piano revives the jam, gets Trey playing notes again, and sends it hurtling towards a very Pink Floyd’s “Time”-like segment? That’s right: Mr. Page McConnell.

When they get back to the second round of jam-closing chords, it completes almost seven minutes of really remarkable and, for Phish, novel improvisation. There’s no tension/release pattern, no build to bliss, no hey-hole cycling every two minutes through different themes. It’s a total full-band deconstruction and reconstruction, building to a crescendo that isn’t predictably satisfying; it’s a neurotic St. Vitus’s Dance Party. It must have really freaked out Trey’s grandma.

The more standard getdown comes in the third part of the trilogy, a Weekapaug that is far less revolutionary, but nevertheless superb. By this point, all four members are flying, able to navigate the song’s aggressive bpm with deceptive ease, trading lead responsibilities almost imperceptibly. From 4:00 - 8:30, Trey’s mostly comfortable dropping back to play rhythm guitar — the original mini-kit — as Page burbles along on his clavinet, another newish piece of gear that will only reach full bloom later in the decade. There are whiffs of the manic mode-shifting of 93 Weekapaugs, even some flashes of Phish jazz, but it doesn’t lean on the tease parade of that era.

All told, it’s a sequence so good it requires me to light the fuse on a narrative I was planning to save for later in the year: The Democratization of Phish. This was a theme that I thought I’d build up to over the course of 1995; that it happened before the end of the year’s first four-show run is a listener’s miracle and a writer’s (minor) annoyance. This process didn’t start in 1995, but I argue it’s the year where Phish made the pivot from “Trey’s band” to a more egalitarian approach, which would go on to bear more fruit over the rest of the decade.

This shift is the likely goal of some of 1995’s easily-visible new features: Trey’s mini-kit and how it forces him into the background, a new batch of songs mostly written collaboratively by all four members, a more even spread of lead vocals. More mysterious is what they worked up in the practice room during those dormant early months of 1995, forcing their improvisation away from the sometimes-stilted “let’s take turns suggesting ideas” structures of fall 94 to a more organic four-way conversation.

They’re not there yet, and they won’t be consistently until the hallowed ground of 1997. A lot of the most treasured 1995 moments come from Trey finding a single partner within the quartet and letting that interplay send them in exciting new directions; think the flat-out macho competitions with Fish to come in the fall and winter. But this Mike’s Groove, improbably, provides a glimpse of what’s to come, similar to how the Bomb Factory feels like a beacon from Fall 94 teleported six months backwards in time.