Kill Yr Idols

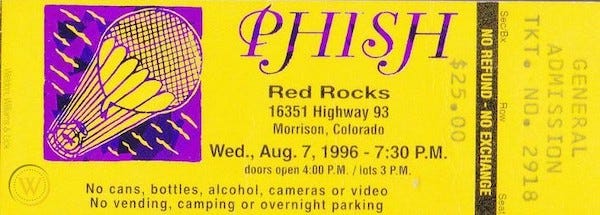

8/7/96, Morrison, CO, Red Rock Amphitheatre

SET 1: Punch You in the Eye > Sparkle > Stash, Ya Mar, Gumbo, Taste, Lawn Boy, Ninety-Nine Years (and One Dark Day), Hold to a Dream, Doin' My Time

SET 2: Runaway Jim -> Gypsy Queen -> Runaway Jim > Free, Colonel Forbin's Ascent > Fly Famous Mockingbird > Possum, Life on Mars?, You Enjoy Myself, Hello My Baby

ENCORE: Bouncing Around the Room, Golgi Apparatus

The last show of the Red Rocks run felt to many in attendance like the final show Phish would ever play at the venue, leading to something of a funereal vibe. By now, word of the wook/cop clashes from Monday night was out, promoter Barry Fey was in the Denver Post saying that Phish would not be welcome back, and everyone’s suspicions that the Phish Machine was now just too big for the picturesque state park had come true. Trey brought the band’s Red Rocks history full circle by calling back to the giant iguana story of his 1993 Harpua narration in Forbin’s > Mockingbird, and left the crowd with what many interpreted as a finger-wagging of an encore in Bouncin’, Golgi.

But there’s another, broader chapter break in the 8/7 show, one that is similarly related to Phish grappling with how big they’ve become. The center of the show features two of their musical heroes — one in the flesh, and one present through a cover of one of his most famous recordings. Phish is, of course, very familiar with guests and covers. But their attitude towards these two instances feels suddenly like an elevation of status, a meeting of equals instead of a fantasy camp.

The first of these idols is Tim O’Brien, introduced near the end of the first set unceremoniously as “that Colorado native that I told you about.” As a kid about to see his first show and eagerly waiting for setlists on rec.music.phish in 1996, I certainly had no idea who O’Brien was, and I distinctly remember conflating him with the Olympic swimmer Trey shouts out earlier in Ya Mar. Oh that’s nice, I recall thinking, they let the swim dude play some bluegrass with them?

Now I know that Tim O’Brien was a founder of Hot Rize, an influential group that kept rootsy bluegrass traditions alive as country diluted into twangy soft-rock and pop in the 1980s. They’re also the band that originated Nellie Kane, and it would have been a helpful tip for me if Phish had performed that song with O’Brien. But instead they chose a different song from Hot Rize’s self-titled debut (“Ninety-Nine Years And One Dark Day”), an O’Brien original (“Hold to a Dream”), and a Flatt & Scruggs classic (“Doin’ My Time”).

It’s a pleasant segment to close the first set, but it’s also interesting for what Phish chooses to not do in deference to their guest. A year and a half ago, Phish submitted to a public tutoring in bluegrass from Rev. Jeff Mosier, a fine player but not one matching the reputation of O’Brien. Now, playing with the latter, they don’t shift to their acoustic bluegrass setup to support their guest’s mandolin and bouzouki, they just...play electric bluegrass like Phish always does. They do it well — I especially like “Hold to a Dream” with Mike’s backing vocals — but it feels less deferential than previous guest appearances. It’s not that Phish is any less respectful of bluegrass, and it will certainly continue to play a role in their repertoire. But they’re no longer changing their sound to fit the guest or genre, instead asking the guest or genre to fit in with them.

The second part of this “now the pupil has become the teacher” theme comes after the setbreak, as Runaway Jim steers into and out of a significant stretch of “Gypsy Queen,” the Gabor Szabo instrumental that Carlos Santana famously paired with Fleetwood Mac’s “Black Magic Woman.” Though the band had teased “Gypsy Queen” a handful of times before, tonight’s was the first version fleshed out enough to receive official phish.net setlist designation. And it feels like no accident that it comes just a few shows after Phish spent a month opening for the song’s most famous interpreter across Western Europe.

I alluded to it in some of the July essays, and I might be imagining it from 25 years’ distance, but there seemed to be a weird tension between Phish and Santana on their shared tour. Phish sat in with Santana on their first night, Carlos and Karl Perazzo guested with Phish on the second date, but that was it for collaborations, apart from an apparently undocumented Phish sit-in with the headliner on 7/19. Compared to 1992, when members of Phish dropped in almost nightly during Santana’s set, it feels like there was a greater social distance between the two bands in 1996.

I’m positive there was no loss of respect for Carlos Santana, but I also suspect Phish felt more like equals this time around, rather than acolytes. And they prove it back in their home country with a Runaway Jim > Gypsy Queen > Runaway Jim which absolutely rips, to a degree that I’m not sure Carlos’ band was capable of in 1996. Don’t get me wrong, Santana still put on a fine show, but he had also played that Black Magic Woman > Gypsy Queen > Oye Como Va medley roughly 1,000 times by that point, and in 1996 he’s closer to Supernatural than the fiery upstart that stole the show on Woodstock’s second afternoon.

But for Phish, it’s still fresh material, and while they stumble into the song seemingly by accident about 7 minutes into Jim, they’re all in by 8:30 and spend nearly six minutes there, even through a stretch of Trey on percussion. It turns out to be a perfect open-ended song for 1996 Phish to jam on: a driving beat, a quick riff to sync up, and then plenty of open space to color in. While Phish can’t match the rhythmic complexities of the Santana band, even (especially?) with Trey on auxiliary percussion, they can certainly go toe-to-toe with the ferocity of the Abraxas version.

Phish will continue to welcome guests to the stage for the rest of the 90s, though they’ll phase out the process in 3.0, only making allowances for opportunities to play with childhood heroes like Bruce Springsteen. But from now on, there’s a sense that Phish is giving their guest a boost by having them onstage, rather than vice versa; best encapsulated by Oswego, where Son Seals and Del McCoury Band appearances exposed those older, more niche artists to the broader Phish audience. Covers too will also grow less deferential and literal, to the point that some will become jam vehicles, a phenomenon that was rarely seen in the early 90s. 1996 is all about Phish growing up, in good ways and bad, and part of growing up is surpassing your parents, your idols, and the previous generation.