SET 1: Chalk Dust Torture, Ya Mar, Split Open and Melt, Waste > David Bowie, Hello My Baby, Good Times Bad Times

European audiences don’t always roll out the welcome wagon for American musicians. Recently, on my other obsessive jamband project, the 36 From The Vault Podcast, we covered perhaps the most infamous example: Dylan’s 1966 tour. The future Nobelist was heckled across the continent, climaxing with the “Judas” incident in Manchester, England. But practically every show contained some form of artist vs. audience antagonism, including a contentious Paris stop on Bob’s birthday played in front of a big honkin’ American flag.

While Phish’s stop in Gay Paris doesn’t have a fraction of that middle finger energy, it does have a pretty feisty crowd. As the full show video (!) shows, Phish played to a room of enthusiastic fans up front and an unseen mob of disapproving whistlers off camera. Thanks to watching a great deal of European soccer, I know that the whistle is not a term of “woo hooo!” endearment over there, but rather a piercing statement of disapproval. And based on that knowledge, I can tell you that the French really, really do not like Phish performing Hello My Baby acapella.

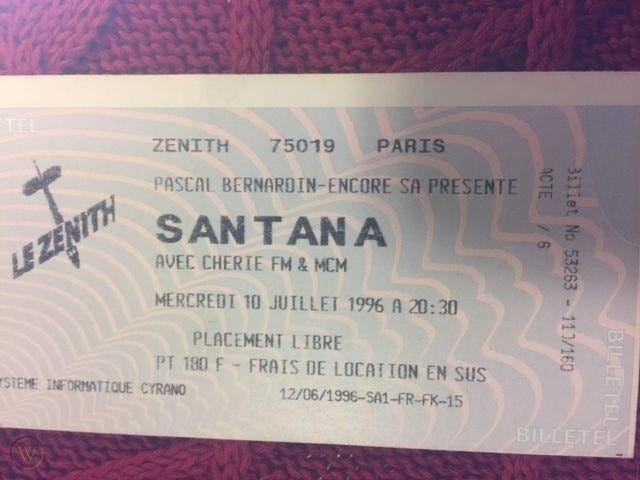

Now, it’s pretty absurd to compare Phish’s faithful rendition of a vaudeville novelty tune written in 1899 to Dylan sneering out “Ballad of a Thin Man” in 1966. There’s no sacred fan preconception that Phish is violating, akin to Dylan “going electric” and rearranging his old, folky material for a full Band. Most of the people there to see Santana probably had no idea who Phish was going in the doors. It’s likely just the default aggression an audience shows for any opening act that is keeping them from the band it actually paid to see. The escalation of fury over Hello My Baby may just have been the crowd feeling betrayed that Phish wasn’t actually done when Trey and Mike put down their guitars.

But there’s a bit of “play it fuckin’ loud!” to the band’s response: going back to their guitars and playing one more song instead of clearing the stage. Even if that song is, diplomatically, a Led Zeppelin cover that most Santana fans would surely recognize and enjoy, the performance has a little extra oomph, with Trey extending his solo for a few extra rounds before they finally take their bow. Trey’s usual little fist pump as he leaves the stage even seems a little more defiant than friendly this time around. It’s the first time in my entire listening project that I’ve heard them deal with such a hostile audience.

However, that intensity is not just a response to the Hello My Baby abuse, but pervades the entire show (okay, maybe not Waste). A week into the European tour, Phish appears to have figured out whatever backstage ritual they need to hit the stage running like they’re already mid-show — I like to imagine them playing a full warmup set just for themselves in their dressing room so they can bring a second-set energy to their allotted 45 minutes. The Chalk Dust opener is a worthy bookend to that fiery GTBT closer, and any set that fits both Melt and Bowie into less than an hour is going to rattle some skulls.

The band doesn’t sleepwalk through either of these jam vehicles either. Melt isn’t really possible to phone-in (even Coventry pulled itself together for the jam), but this one has some extra spice at the end, where Trey plays intentionally clashing chords over the song’s final minute. Bowie, meanwhile, is stuffed full of interesting ideas, the first non-guest-enhanced performance of the summer to earn a jam chart slot (and the last Bowie to do so for all of ‘96!). Trey finds an alternate chord progression pretty early in the jam, maybe a hint of slow-motion “25 to 6 to 4,” and the whole band follows for a couple minutes before they howl back into Bowie classique.

It’s not nearly as transformative as the half-hour Bowies of the previous summer, but it still tinkers with the formula in a way that 95% of the Zenith audience wouldn’t notice, even if they weren’t too busy whistling. Despite all the new-market outreach this month is supposed to accomplish, Phish are still doing things, whether it’s off-model Bowies or nightly barbershop routines, to entertain themselves and the handful of people who followed them abroad, no matter who it annoys. Like Dylan in Europe 30 years earlier, they’re not afraid to come off as confrontational — or maybe more, in Phish’s case, dorky — and let everyone else play catch up.