SET 1: I Am Oysterhead, Mr. Oysterhead, Jam > Rubberneck Lions, Owner of the World, Happiness in My Pants, Wildwood Weed > Sinkin' Down, Pseudo Suicide

ENCORE: Immigrant Song, The Israelites, All Day and All of the Night, House of the Rising Sun

The power trio is among the most sacred forms of rock band structure – you never hear about power quartets or power decets, Godspeed You Black Emperor notwithstanding. But within the power trio category there are two distinct flavors. There’s the Star + Two Other Guys model, traced back to the Jimi Hendrix Experience, where a distinct figurehead fills up all the space afforded by the stripped-down lineup. Then there’s the Throuple of Equals model, where three superstars attempt to balance their talents and egos with a tripod structure – think Cream.

For Trey’s first two significant extramural projects, he was drawn to the power trio format. Maybe it’s because they’re inherently low-commitment; the ingredients that make them combustible also usually cause them to flare out fast, due to their precarious interpersonal chemistry. Or maybe the condensed rock instrumentation of the power trio was a welcome break from Phish in one of their most complicated eras, both on and offstage. Whatever the motivation, Trey sampled one of each power trio type, playing the Jimi role with TAB in 1999 and then kicking off 2000 by co-founding the on-again/off-again supergroup of Oysterhead.

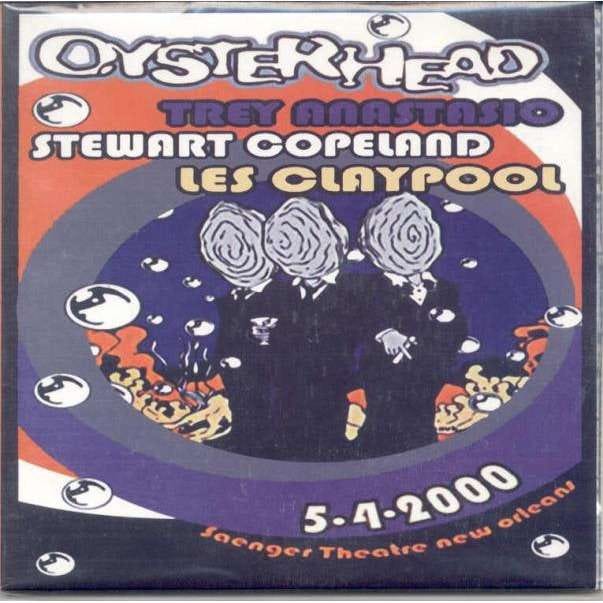

Organized by Les Claypool as a side attraction to that year’s Jazz Fest, the project with Police drummer Stewart Copeland was a very different animal from TAB’s humble origins as the 8 Foot Fluorescent Tubes. The one-night engagement drew feverish demand for tickets and a star-studded audience, attracting the likes of Matt Groening and Francis Ford Coppola. And it stole a whole lot of thunder from the actual Jazz Fest that day, where underwhelming and embarrassingly of-the-time acts such as Better Than Ezra and Big Bad Voodoo Daddy were the main stage attractions.

How you apportion the credit for that hype is an interesting snapshot of Phish’s curious status at the dawn of the century. One could easily argue that Trey was the least famous of the Oysterhead Three, with Primus having tasted the alt-rock radio success that Phish never found and The Police being merely one of the biggest bands in the world for a few years. As Claypool teases him a couple songs in: “I’m in a band that’s somewhat popular. That guy that back there was in a band that was extreeeemely popular. And I’ve been sitting around, scratching my head, trying to figure out, where the hell did you come from?”

And yet, Claypool later laments that Phish fans gobbled up all the tickets before Primus fans had their chance, and the crowd is clearly in Trey’s corner: you can hear it in the cheer for Les’ Reba quote – flubbed lyrics and all – vs. the polite response to a similar “Jerry Was a Race Car Driver” nod. Nevertheless, Trey seems to defer to his more traditionally esteemed colleagues, ceding the ringleader role to the much chattier Claypool at this debut date. Musically, it’s also tipped towards the bassist; you wouldn’t mistake Oysterhead’s material for Phish and certainly not for The Police, but it could easily pass as a Primus side project, at least in this raggedy debut performance.

That’s mostly due to Claypool’s distinctive style; he’s a musician who, to both his credit and detriment, can’t help but sound like himself. And that distinctive presence casts Trey in an interesting role. On Primus records, Claypool’s aggressive and melodic bass squeezes guitarist Larry LaLonde to the margins, where his job is to provide atmosphere and color. I remember listening to Pork Soda in 1993 and thinking the guitarist doesn’t really do anything, a very dumb teenage boy opinion. To my ears today, he’s the most interesting part of Primus’ mid-90s peak, smuggling Adrian Belew noise sculptures into the band’s novelty hard-rock.

Since late 1996, that’s familiar territory for Trey as well, and Oysterhead offers him the opportunity to indulge that more abstract side without having to simultaneously hit his expected guitar god marks. The bespoke Oysterhead material lets him utilize all the textural tricks he’s developed over the last three years in a setting custom-made for them, rather than trying to blend them into classic Phish songs with mixed results. Even the TAB songs didn’t offer him so much freedom to shoegaze in the background; when the band is your namesake, you’re gonna have to provide some guitar solo fireworks.

So the most interesting part of this show featuring Oysterhead in their raw (har de har) phase is hearing all those recent post-punk Trey moves in a new light. The band walks on stage to the kind of pre-recorded Trey drone he’s still deploying to this day with Atriums, and the pedal-crazed “I Am Oysterhead” solo is straight up Remain in Light. Throughout the set, he slathers just about every song in bweeoooos and even plays only synth – with some presets very familiar to Phish fans – for the entirety of “Sinkin’ Down.” When the band improvises, most notably in the long Floyd-y intro to “Rubberneck Lions,” he sounds like he’s following Claypool’s lead and adding embellishment instead of charting the course.

But yielding so much control to Claypool steers Oysterhead into dark waters. The Phish and Primus Venn diagram overlap sits squarely in the Frank Zappa catalog, but Claypool’s various projects have always embraced the composer’s cruel sense of humor, an aspect Phish avoids – no coincidence that their go-to Zappa cover is an instrumental. There’s a nastiness to Primus that doesn’t suit Trey, even at the dawn of his rock-bottom decade.

With Claypool handling a majority of the lyrics and vocals, Oysterhead inherits Primus’ edgelord rep*; even “Owner of the World,” the latest of Trey’s loving tributes to his usual drummer, gets a lecherous edge when Les chimes in on the chorus. The contrast is in sharp relief on “Pseudo Suicide,” a real trigger warning of a song that’s interrupted by Trey singing about cheesesteak and pie, or “Blue Ginger,” a gorgeously fingerpicked, William Tyler-esque instrumental used as a lead-in to a song called (sigh) “Happiness in My Pants.”

Though the Oysterhead experiment was deemed successful enough to eventually inspire a studio album** and a full 2001 tour, its musical influence won’t hang over Phish 2000 the same way TAB did in 1999. If anything, it just further propelled Trey down the path he was already on towards ever noisier and denser swirls of guitar effects. Instead, it’s the scuzzy, bad-acid vibes that would linger – a year that’s roughly bookended by appearances with Les Claypool and Kid Rock aligns Phish, at a particularly fraught moment, with the ugliest impulses of millennial music, more Ozzfest than HORDE. And in the wake of Big Cypress and its long shadow of “what do we do next?,” it offers up a foreboding answer that would haunt Phish all year: maybe it was time to see other people.

* - I was feeling a little uncharitable about my Primus feelings, and then they released a song called “Little Lord Fentanyl” two days before this essay went out, so…I stand by it.

** - Where Trey’s fingerprints are much more audible on songs like “Oz is Ever Floating” and “Radon Balloon” – surprise, surprise, I like it better than this show.

The best part of that show was Garage A Trois opening for Oysterhead.