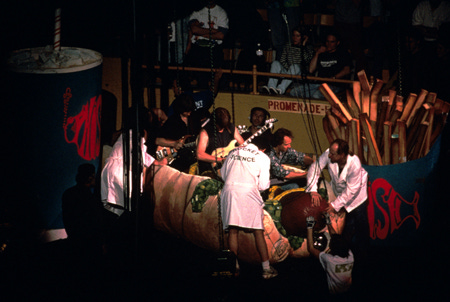

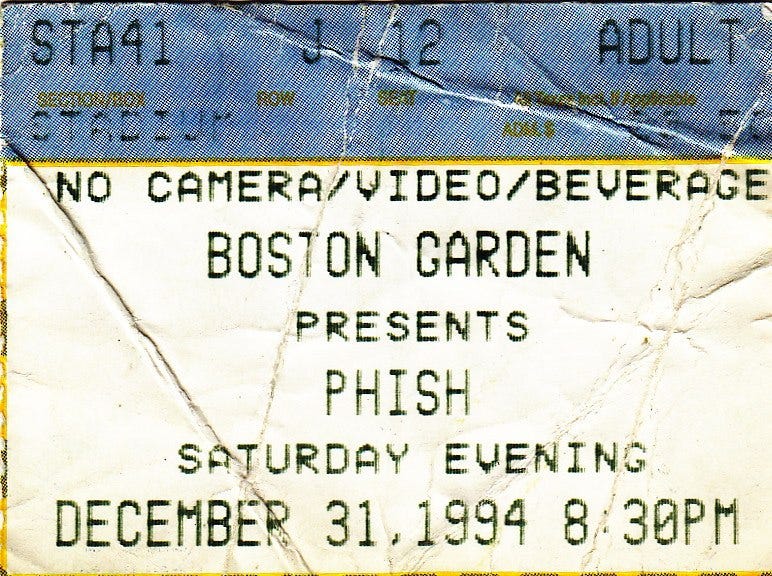

The flying hot dog has become such an iconic symbol for Phish that, like most icons, a lot of the nuance behind it has been lost. It’s a quintessentially Phish image, so silly that you either accept it as a fan of the band and its inherent sense of humor or it makes you reject them entirely as corny nerd shit. Recall that 1994 is the turf of late grunge and gangsta rap, the year of The Downward Spiral and Ready to Die, Kurt Cobain’s suicide, the mud and commercialism of Woodstock ‘94, and The Eagles’ “Hell Freezes Over” reunion. Dark times! And here’s Phish, flying around the Boston Garden inside encased meat to a Captain Beefheart song.

But the hot dog stunt wasn’t just Phish being musical contrarians in the over-serious musical culture of 1994. As both the Long May They Run and After Midnight podcasts touched on, the gag was built as a solution to the band’s greatest anxiety at this stage of their career: how to preserve the intimacy of the Phish live experience while playing the country’s largest venues. The starting point, as Trey told both podcasts, was finding a way to give the fans with the worst seats in the arena a close-up view of the band, if only for a few seconds. Several layers of absurdity later, they ended up in the hot dog, throwing ping pong balls to people in the rafters.

Obviously, repeating that maneuver every night wasn’t a sustainable option, for both technical and musical reasons — I’m sure it was fun in person, but on tape, the lengthy pauses to get the band safely in and out of the dog are a real momentum killer. Instead, the band needed to find other ways to make basketball and hockey arenas feel like a Burlington bar. Somewhere between the band’s first Madison Square Garden appearance and its 61st, they succeeded.

“The relationship that we have with Madison Square Garden has exceeded the relationship that we had with Nectar’s, which is pretty incredible,” Trey recently said on their satellite radio channel. “I feel like I’m at home, I could put a bed in that place at this point...it’s the most comfortable room that we play in at this point in time.”

In this holiday show at the other Garden, you can hear the band working through musical methods of building that intimacy, even with 16,000 people staring them down. While it’s the theoretical climax of the run, it sounds quite a bit looser than the previous night’s debut at MSG, which takes the form of some strange setlist and pacing decisions. None of the night’s three sets go past an hour, and there’s a handful of semi-rarities such as Glide, Funky Bitch, and Buffalo Bill, two different a capella religious hymns within three songs, a guest appearance by Tom Marshall, and two songs left incomplete due to the midnight gag.

Of course, all that only sounds strange in the context of when the show happened. I’m writing this from the midst of the 2019 New Year’s Run, where they’ve already managed to debut 2 songs, play some unholy amalgam of Ass Handed, Guy Forget, and Chalk Dust Torture Reprise, do their ridiculously convoluted Turtle in the Clouds dance, and oh yeah, play a 36-minute Tweezer. But in the early 90s, the biggest shows often found Phish on their best, normal (by their standards) behavior. Compare this NYE setlist to a year ago, played at the smaller Worcester Centrum but also broadcast live on Boston radio, when the band hit all their expected marks: Reba, Antelope, Tweezer, YEM, Hood, check check check check check.

The band easily could have done that again in 1994 — there isn’t a “no repeats” rule on the NYE run yet — but perhaps they recognized that taking the predictable route would just exacerbate the new distance between band and crowd. Playing the oft-requested Funky Bitch (even if it doesn’t quite work as a set closer), bringing out their lyricist and “Mike's maternal grandmother, Lillian Cherry,” who “joined the band on stage for Chalk Dust with a shoe in her hand,” and just generally indulging their deepest in-jokes on such a major stage is an effective method to make the Celtics home court feel like the home of gravy fries.

There are other tricks the band could’ve used to preserve that connection; in fact, they created a bunch of them for the last big venue jump, from clubs to theaters in 1992. That transition yielded the Secret Language, first explained from the stage in March, and the Big Ball Jam, which debuted at the then-impressive 2500-capacity Ross Arena in November. But for logistical reasons, these weren’t going to work at the next level up — you might never see those big balls again after throwing them into the Garden pit, and I’m not so sure people want to “All Fall Down” on those floors either.

By next fall, they’ll have concocted the nightly Chess Move as a way to keep the band and fans in contact via friendly competition. Much later on, they’d flip the seating chart on New Year’s Eve again with the Flatbed Truck and Hourglass sets (not to mention the hot dog’s 2010 return) at Madison Square Garden. But mostly, they’d let the music do the work of maintaining intimacy, trusting their fans to be close listeners and fluent with the most obscure corners of their catalog, so that even the most esoteric onstage decisions would be followed by at least some of the fans in the crowd.

In this sense, rewarding the small percentage of people who knew Buffalo Bill on only its third performance ever is another, more abstract method of giving a group of fans the “best seat in the house” momentarily, one that requires a lot less safety equipment. And like most NYE shows, there’s not a lot of deep improvisation on this night. But there is some extra credit work throughout, most notably on a long, loopy Maze, but also in how the third set’s Chalkdust and Suzy charge right past their normal ending point, moments which are duly noticed and celebrated by the sold-out Garden crowd.

It’s a thread that goes all the way through time to the Baker’s Dozen, where Phish used the other Garden as their personal clubhouse for one of their most ambitious experiments, trusting the audience to hang with all the donut flavor jokes, lack of repeats, and extended versions for 13 nights. That’s the run, more than any of the many, many New Year’s stands, that likely clinched Trey’s comfort in the World’s Most Famous Arena. But the seeds of making themselves, and their fans, feel right at home in even the biggest venues were planted 25 years ago, thrown from a flying hot dog.