Primary Sources

6/19/95, Noblesville, IN, Deer Creek Music Center

The calendar flipping over to 1995 provided this project with a new dimension: ample documentation. 1993 and 1994, despite being very well-lauded years of Phish, still retain some of the fog of Phish’s early days, with little information beyond the setlist available online, very rare photos or video footage, and even occasional shows without a recording in circulation. Usually just the music is enough, but in the marathon pursuit of how Phish became Phish, it’s sometimes frustrating to have so little context — often I feel like the historical record is more clear on 50-year-old Dead shows than Phish shows from the early 90s.

But starting in 1995, the Phish archives are a lot richer. My difficulty in finding any trace of the original venue for 6/8/95 aside, most of the summer shows have left data breadcrumbs on the internet, including actual show photos and video from heroes who snuck big, clunky VHS camcorders into venues. The ability to put some images, however heavily pixelated, on top of the Red Rocks Mike’s Groove or the Mud Island Tweezer has been a fascinating bonus as I try to reconstruct what was happening this wild summer.

This week, that good fortune really hit the jackpot with the official premiere of video from 6/19/95 on Phish’s pandemic distraction/fundraiser, Dinner and a Movie. While I’ve been staying about a week ahead of publication in writing these essays, I made an exception for the opportunity to watch a full show professionally shot, instead of getting motion sickness from a guy in Row ZZZ hiding from security.

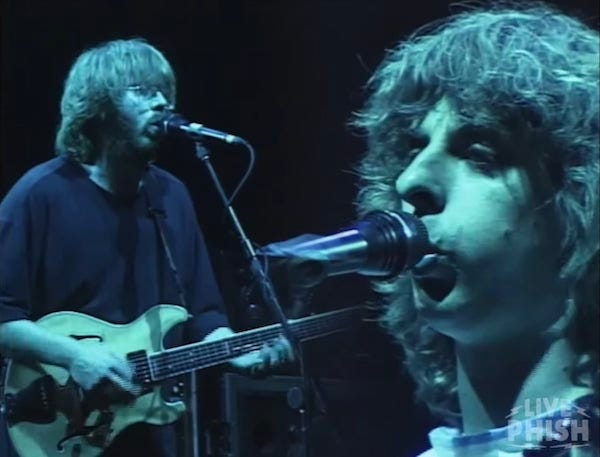

First of all, the venue feed from Deer Creek was unexpectedly competent. They didn’t really need to do much more than beam some static close-ups out to the lawn screens, but whoever was in the director’s chair really earned their salary, generally finding the right musician to feature in the middle of complicated songs and improv, and utilizing a cross-fade split-screen effect to cram multiple members into the same shot. Thankfully, 90s Phish never discovered the Video Toaster effects that have been an amusing distraction to the Dead’s counterpart Shakedown Stream, giving us a nice, clean view of the band (at least until the film crew clocked out midway through the encore).

That gorgeous 480p quality allowed all of us to see, first and foremost, just how unbelievably dorky Phish still were in 1995. My god. Trey’s still wearing his classic combo of enormously-oversized black shirt and shiny gold pants of indeterminate fabric, Fish has got on an alternate banana-print muumuu and his Chris Sabo rec-specs, Mike is dressed like a waiter at a beachside restaurant called Crabby McCockles (pleated white shorts!), and Page is dressed like...well, like me in 1995, to be honest.

Their sartorial choices are an easy target, but also weirdly significant. If one of the main questions of Summer 95 is how far they’ve grown from the previous year, it’s a pretty potent symbol that Trey is literally wearing the same clothes he wore for Halloween 94 and on Letterman. And for a year where they’re learning how to get comfortable with being genuine rock stars, it’s instructive to see that they don’t look the part in the slightest; the state of their haircuts alone, a mere two weeks into the tour, is testament to how little they care about their image, even in front of 20,000 people.

The Phish stage setup of the time was also amusingly low-rent for a venue also visited by The Eagles, Van Halen, and, infamously, the Dead the same summer (a much better-coiffed Yanni played there the night before Phish). In the few overhead full-stage shots doled out by the Deer Creek crew, you can see that there’s no rugs, just some duct tape on the stage to help them hit their lighting marks. We got a few shots of the Minkin scrims and just a little bit of the lights, not enough to fully appreciate the multimedia experience of a 1995 Phish show, but enough to see that Kuroda’s technology has come a long, long way. The band has a minimum of gear: Trey’s little wooden amp cabinets, a couple pedal boards, Fishman’s kit is still a reasonable size, Page only has five keyboards.

Which makes it all the more impressive that they can produce such a massive sound from a setup that hasn’t progressed that far from their club days. As many commented during the live Twitter discussion, this Deer Creek stop is not considered one of the highlights of the summer. But it still includes casually great performances of all its featured pieces, such as Reba, Antelope, Bowie, YEM, and Possum, and rarer treats such as Tela and The Mango Song. It’s got that effortless confidence that I talked about for Lakewood, a band that simply knows how to slay its material on a nightly basis.

Given that sonic self-assurance, what’s perhaps most striking visually about these moments is the body language, or more accurately, the lack thereof. Apart from Trey, there’s very little movement on stage: Mike is a statue, Fish and Page are surrounded by their instruments, only venturing out for a late-show Acoustic Army. But Trey tries to provide enough stagemanship for the whole quartet, bouncing around with nervous energy, pacing forward and back at the height of the Bowie jam, doing his rooster strut during YEM. It’s like he’s the only one who fully believes that they’ve earned their place on these big stages (costuming aside).

All this onstage stoicism also contributes to the other unsettling body language of Phish in 1995: the almost complete lack of eye contact between band members. In general, Mike looks at nobody, Page stares out from his piano (which is pointed at the other three in this era) but nobody looks back, and Trey and Fishman occasionally egg each other on and bicker — check out the power struggle over the tempo of Rift, which just sounded flubbed on tape, but video reveals to be Trey scolding his drummer a little too intensely. The editing makes it all seem much more affectionate than reality, with the split-screens creating the illusion of intimacy.

The deeper the improv, the less they interact; I dare you to find a single point in the 23-minute Bowie (a sublime version with a recurring descending theme that could soundtrack an 80s action thriller) where a band member acknowledges a peer’s existence. The lack of body language is in sharp contrast to the other 1.0 show aired by Dinner and a Movie, 7/21/97, where Trey was constantly conducting the band with hand signals and off-mic exhortations at the dawn of cowfunk.

But of course, they are paying rapt attention to each other in 1995, it’s just entirely aural, not visual. A news clip found by reader Josh from later in the summer quotes Page on their rigorous practice schedule before this tour started: “For the two months prior to this tour, we spent five hours a day, five days a week practicing, getting ready.” Phish Twitterati with more learned ears than myself mentioned hearing explicit “hey hole” exercises at several points in the show, including in seemingly straightforward jams such as AC/DC Bag. The lack of body language isn’t a sign of bad band chemistry, it’s the reverse: a deep listening so intense it almost looks like a trance.

[Last screenshot from Jam Sandwich, who also made some excellent GIFs.]

I'm sure you've noticed in the 12/6/97 Tweezer how incidentally played the best parts seem to be... When Trey hits what is for my money the best riff he's ever played, he doesn't even look around, if I recall. Or the way he plays Mike's Song during the Clifford Ball without looking at Fishman much. It always blows me away to see that.