I’m still hung up on the Page quote from The Phish Book I used yesterday. It’s such a candid appraisal of Fall 94, and there’s a lot to unpack. Here, I’ll save you a click:

We don’t play Tweezer as much as we did a few years ago, when we were consciously trying to stretch our jams out. Tweezer lent itself to that very well. We didn’t intend to make the Bangor Tweezer [11/2/94] half an hour long. On the other hand, there have been David Bowies where we said, “Let’s see how far we can stretch it out.” It takes a conscious effort sometimes, since we were inclined to play ten- or fifteen-minute Bowies and not take that extra ten or fifteen minutes. Once in Dallas [5/7/94] we decided to play Tweezer for the whole set, which was probably the beginning of our whole extended-song thing. But a lot of those jams weren’t very good in the end. When we were choosing material for A Live One, I’d hear these Bowies, Tweezers, and Antelopes and think, “That’s a good moment there, but man, the next five minutes kind of drags.”

Yesterday, I used the quote to talk about the intentionality vs. spontaneity of jamming, but today I want to focus on the last part, the self-appraisal that portions of those jams were less than successful. In November 1994, the appearance of extended, open improv is still a relatively recent development, and since the Bangor Tweezer they’ve been pushing it fairly hard. With a little bit of fuzzy math (counting that Have Mercy in the 11/12 DWD, for example, but not YEMs, even though they have been getting longer themselves), the second leg of Fall has included five songs in ten shows that went 20 minutes or longer, a milestone that was exceedingly rare before that point. The Phish fan natural instinct is to assume that once the stopwatch goes past 20 minutes, that means it’s a classic. But in these early stages of Type II jamming, the truth is more complicated.

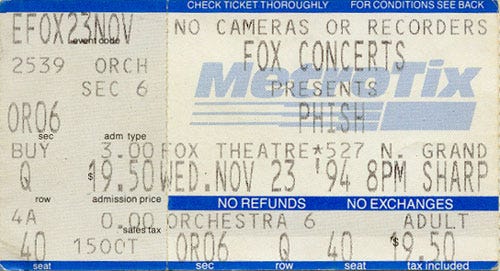

Consider this night’s Tweezer, which just pips past this mark, clocking in at 20:01. As Page said, Tweezer and Bowie are the primary laboratories in which Phish are trying out their new longform approach. Pre-planned jamming or no, there seems to be a collective decision in these songs to loosen their grip, steer into any promising tangents that present themselves, and treat dead ends like cul-de-sacs — not the end of the route, just a pause. It’s an experimental approach, and the whole point of experiments is that they’re going to fail as often, if not more, than they succeed. Especially this early in the process, when their instincts aren’t so good about which leads to chase down, how to satisfyingly fill the transitional spaces between more developed themes, and perhaps most important, deciding when to stop.

That leads to performances like this Tweezer, which alternates between awkwardness and awesomeness for its full duration. The jam starts out on pretty standard Tweezer footing, until Mike nudges it in a darker direction around 7:00. But that suggestion doesn’t take, and like the Funky Bitch the night before, the band comes to an almost complete stop, maybe the clearest signal that they’re still figuring out how to sustain an open-ended improvisation. For a couple minutes, it’s hushed and sparkling, reminiscent of the early sections of Hood jam — not a resemblance you’d normally hear in the typically thorny/swaggery Tweezer jams of the era. It’s not until 10:30 that it starts to swell again, riding the back of a Trey drone, until it explodes into a glorious peak around 12:30. It’s no faint praise that this brief segment reminds me of my favorite Tweezer ever, 12/6/97, in its majesty soaring out from darkness, just with the thinner sound of their 1994 gear and a much more intimate venue setting.

There’s more of interest after that peak; at 14:20, intriguingly, it sounds like Birds of a Feather for 10 seconds, 3-½ years before the song’s debut. But then the wheels fall off. It seems like they all choose four different directions and can’t sync back up — accidental free jazz. Trey abandons ship at 16:30, returning to the Tweezer theme, and there’s a rather ham-fisted run-through of the song’s classic conclusion filling up the last few minutes.

As a whole then it’s unsatisfying to my taste, even if the high points are very high indeed. There’s an inconsistency to this and other early long jams that they hadn’t yet figured out how to overcome, creating a different axis of tension and release: the struggle between incoherence and symbiosis. Later on, and to this day, almost every extended jam will have at least one period of indecision while they wait for an idea to jump on, but they get much better at papering over those fallow sections with a crowd-pleasing vamp — Fall 97 is a great example of this, with an arsenal of danceable funk themes that are almost like hold music (very good and fun hold music!) until inspiration strikes. In some cases, the long Fall 94 jams are also an argument for the modern ripcord; wouldn’t this Tweezer be more memorable if it segued out at minute 14, rather than limping towards a conclusion for several minutes? One of the hardest collective decisions to reach, in any form of improv, is “we’re done, let’s wrap it up”...sometimes ripping off the band-aid is the better option.

It’s unreasonable to expect them to have these instincts and skills right out of the gate, and in Fall 94, they’re still at the point where they’re feeling out just how far they can push songs and not lose the plot, or the crowd, entirely. That they probably overshot this point fairly often isn’t really a criticism; it’s a testament to their scientific method, and how they learned from negative results.

[Stub from Golgi Project]