Just as the best Phish jams have a narrative, so too do the best Phish tours develop a dramatic arc. In their most celebrated years, the band sounds very different at the end of an itinerary than they did at the outset; not for nothing are the two highest-regarded months in Phish history Decembers. When all the ingredients are in place, going into the test kitchen of the concert stage each night can produce some incredible real-time advances.

As we near the end of Summer 95, I’m still undecided on whether it is one of those tours. Certainly, it is experimental, with the band pushing the boundaries of their improvisation on an almost nightly basis, fan approval be damned. But I’m not hearing a lot of progress from night to night in those big jams, and with the foreknowledge that they’d largely disappear by the band’s next tour, they feel like they’re charting the path towards a dead end.

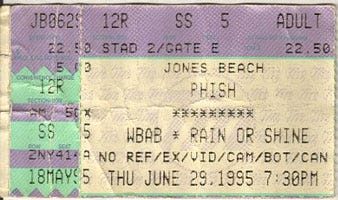

This show’s improv centerpiece is David Bowie, the most frequent vehicle this summer for the band’s explorations of darkness and dissonance. Bowie’s size has swelled gradually over the course of the summer, from a 15:44 version at Red Rocks to tonight’s 28:06 and, later this week, inching past the half-hour mark at Sugarbush. But despite this time inflation, the flavor of these Bowies has stayed pretty consistent — they aren’t trying out new ideas in each jam so much as seeing how far they can stretch one concept.

The Jones Beach Bowie is a representative example. It starts strong, dropping out of Free with a tantalizing hint of an alternate, chugging Fish beat in the intro, followed by 3 minutes of Page hitting rumbling notes from the far left side of his piano as Trey’s effects howl in the distance. When the main jam kicks off, Mike suggests a series of dissonant, descending lines (think Mind Left Body Jam, but spookier) that are picked up by Trey, and the band spends several minutes nibbling around those edges at subdued volume. By the end of this segment, Trey is just manipulating feedback, until the rest of the band creates a nightmare carousel vibe behind him that slowly builds in intensity for several minutes more.

When that creeping dread finally breaks we’re already into the 19th minute, veering into a deranged mutation of the “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” ending and then a segment featuring Page’s piano that foreshadows Birds of a Feather — not a particularly relaxing song itself. Around the 23rd minute, it starts to hint at wrapping up, though even here it stays cruel, ruthlessly teasing the ending for a solid 3 minutes before it finally arrives, even reverting for a minute to the more standard Bowie jam key for the first time in the performance. There’s no real release to the preceding twenty minutes of tension apart from the pre-scripted Bowie finale.

If this jam had a topography, it’d be a relatively uniform range of jagged rocks; if it had a color, it’d be a saturated dark violet, with only a few sparse flecks of brighter shades. And the same description more or less applies to the rest of this summer’s Bowies. It makes sense that the relatively unsung Riverfront Bowie from way back on June 14th might still be my favorite of the tour, because it does largely the same thing in the relatively tighter time of 17:37.

The obvious antecedent here is the Providence Bowie of 12/29/94, which was the improvisational exclamation point on what the band was developing from November onward. But even that jam, for all its intense horror, offers moments of respite, especially the McGrupp-ish and then ridiculously peaky section from 20:00 to 25:30, just before the infamous Lassie/psychopathic-whispering sequence. None of the Summer 95 Bowies have that kind of beauty embedded within their darkness, and the broader emotional range makes a huge difference.

As a postscript to discussing the influence of A Live One on this summer, perhaps it’s more accurate to say that that album’s Tweezer established the frame but the Stash filled in the content. The earliest performance included on the live album, the 7/8/94 Stash, is a masterpiece of building dissonance, playing notes that sound “wrong” until the audience is beaten into submission, then swooping back in with a refreshing, consonant rescue that returns listeners to the safe confines of the song.

But the ALO Stash is far less sadistic than these Summer 95 Bowies, tantrically toggling back and forth between tension and release until it finally explodes in the final minute. It’s also only 12 minutes, of which the jam is only a little more than half — a much more tolerable length of time for this kind of experiment. Stretching that approach out to more than double the duration and providing fewer breaks asks a lot of the audience, and makes for difficult listens even now, from the comfort of home.

The summer’s unrelenting focus on tension and dissonance brings me back to the band’s pre-tour self-description as “Sun Ra meets Velvet Underground at a bluegrass festival. In the middle of Appalachia...in the middle of a scene from Deliverance.” Certainly VU were not a band given towards happy endings; you’re not going to find a satisfying release in the half-hour “Sister Ray”s of The Quine Tapes either. Sun Ra was once quoted as saying “Anyone can make sense playing in tune. But can you make sense playing out of tune?” However, there is a groove to those VU jams and to even the most outré of Sun Ra music, a concession to listenability that Phish, in their Summer 95 extremity, mostly avoided.

At this stage, Phish could play the beautiful — almost too easily — but they were more interested in stretching out the ugly side of their improv until they found the breaking point. It was almost inevitable that Dave’s Energy Guide, one of the band’s earliest experiments in dissonance, popped up for the first time in 4 years in the middle of the 6/28 Tweezer. Perhaps these excavations were also part of their self-aware mockery of arena/shed rock, a resistance to the “easy path” of playing big, satisfying rock music for giant crowds. If that’s the case, it’s a hang-up that will disappear by the fall, providing a way out of what is starting to feel, by the end of the summer, like a cul de sac.