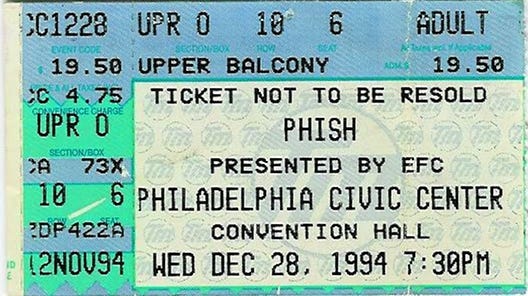

The holiday run of 1994 would be punctuated with perhaps the most famous Phish gag in their entire lore: the flying hot dog. But the arena shows leading up to that historical moment also reportedly had something special. Where the NYE Run of 1993 had the aquarium stage, the 1994 run allegedly had a much more subtle tweak to the Phish technical setup. In fact, it’s so little known, it’s literally a footnote to Phish history, as basically the only documentation of it is a sentence in Kevin Shapiro’s show notes:

This was the first known Phish show to employ quadraphonic sound, with speaker stacks at each of the four corners of the venue.

A similar note appears on all four shows of this run. But even that small piece of information is in dispute. For one thing, multiple people have sworn to me that the Halloween show in Glens Falls deployed a quadraphonic setup two months earlier, and this rec.music.phish post from a few days later appears to agree. For December, there aren’t many contemporaneous posts discussing its usage, and it turns out Phish fans’ memory of shows they attended 25 years ago are somewhat hazy...go figure. Here’s one from Phil Nazarro on January 2, 1995:

didn't anyone notice that the sound system was in quad configuration? this isn't new? most people weren't happy with the sound, but where i was sitting (3/4 of the way back, on the lower level) i was more than excited about the sound. i've seen other bands with quad sound and it didn't work nearly as well. most of those 'spacey jams' you are hearing about where (imo) a way of showing off/testing this system and they worked great. The music swirled around the garden in an audio 3d manner.

Another fan posted about the 12/29 show:

When I was at this show [this was the "longest" (1st or 2nd ever at the time) Bowie at the time] we couldn't believe that we heard what we heard. The acoustics inside the venue were setup in a pretty decent quadrophonic sound so during the spaciest parts there were just crazy electronic loops going all around the Providence Civic Center.

Sounds like proof, right? But in order to get more context on this experiment in sound, I sent some questions directly to the one man who should know: Paul Languedoc, Phish soundman up until 2004. He graciously wrote back, but his response only muddied the waters further:

Unless I have a huge memory hole about it, the only time Phish employed a true quadrophonic sound system was during the “Quadrophenia” Halloween show in 1995. We did routinely hang delay speakers as reinforcement in the larger rooms, but these were pointed toward the back of the room and carried the same program as the main speakers. This may be what Kevin S. is remembering. Later when the PA system improved enough to make the delay speakers unnecessary, we did hang what I would call effects speakers in two small clusters about even with the FOH position. These were mostly for reverb and the like, and I also placed two extra microphones in the top of Page’s Leslie for these speakers.

I may be wrong about the timing of all this, we may have had effects speakers at the shows you mention, but I don’t have memories of true quad sound at those shows. You would only do it if there was program on tape (at the time) as at the “Quadrophenia" show, or maybe some weird guitar effect. I hope I’m not deflating a myth, I just can’t corroborate other people’s memories of these shows.

I’m inclined to believe Paul above all the other sources here, so what’s going on? Perhaps it was just a trick of the ear, resulting from a combination of the delay speakers, the echo-y acoustics of venues designed for sports, and the deep weirdness Phish reached at certain moments of this run. The fact that most people remember it best during the Providence Bowie fits this theory — one can easily imagine the delay loops and eerie whistles of that performance bouncing off the concrete walls of the Civic Center and tricking some fans into thinking it was an intentional sonic choice. There’s maybe a Mandela Effect at play here too; by the end of 1994, Phish sounded like the kind of band that would be using quadraphonic sound, so logically, they must have?

Essentially an early version of surround sound, quadraphonic setups utilize four channels instead of the typical two of stereo. With speakers placed in the four corners of a room or arena, a recording or performance can create a more immersive experience. The first quadraphonic concert performance is credited to, no surprise, Pink Floyd, who deployed an early version of surround sound for their famous Games for May concert in 1967 (Check out this amazing piece of 60s tech they used to control the sound). Floyd also pioneered quadraphonic album releases meant for home listening, using it most famously on Dark Side of the Moon, but in the early 70s just about everyone was doing it, before the market for quad stereo equipment cratered.

By 1994, quadraphonic systems had been eclipsed by home theater “surround sound,” but were still used in concert settings — Pink Floyd, in fact, used a 200-cabinet version for their Division Bell stadium tour that year. So if Phish wanted to use a similar (though much smaller and less expensive) setup, the technology was out there. But they also would’ve needed a musical reason to go four-channel, with all the extra effort that requires.

Happily, 1994 saw Phish transforming themselves into a band that could take advantage of those bells and whistles. Up through 1993, it’s actually kind of misleading to describe Phish as “psychedelic” — they’re too hyper, too proggy, too clean-sounding to melt brains (without pharmaceutical assistance). But from the Bomb Factory through the long jams of fall, they began to explore a more atmospheric sound that begged for sonic immersion. Trey has his new effects, including the digital delay loop pedal that would prelude tomorrow night’s Bowie, and noisier approach. Page has his oscillating Leslie speaker, which Paul mentions above, a piece of gear that Trey would also start using around this time. And both the NO2 appearances of summer and the deep fall jams found all four using unorthodox instruments for sonic color: Trey’s megaphone, Mike’s drill, Fish’s vacuum, even the stage fans.

That experimentation carried over to the holiday run, whether it was enhanced with extra speakers or not. On this night, there’s a stretch of Mike’s Song starting around 6:00 when Trey’s doing his siren-drone schtick and, quadraphonically enhanced or no, the crowd goes nuts for it. A bonkers 17-minute Weekapaug gets even stranger: there are some high-pitched loops flying around the background in the sixth minute that sound almost 98/99 vintage, some odd, sparse sections that recall the Bangor Tweezer, the first “Auld Lang Syne” tease of many this week, and the most triumphant/deranged version of “Little Drummer Boy” ever played.

The rest of the run contains additional moments that would have benefitted from the quadraphonic system, if it truly existed. There’s the Providence Bowie, of course, but also one last far-ranging 1994 Tweezer and a leisurely YEM on 12/30, and a loop-riddled Maze on 12/31 (not to mention the offstage conversation that set up the gag). That said, if quadraphonic sound did exist for the NYE run of 1994, it’s a little weird that it didn’t come back. OK, the next tour would be in outdoor venues, where the effect likely wouldn’t have translated as well. But then reviving it for the cover of Quadrophenia made sense for both thematic and musical reasons, so why not use it the rest of the fall tour? As far as I’m aware, the closest thing to a “surround sound” PA they’ve used in recent times was the bespoke setup for the “Storage Jam” at 2011’s Superball.

In the end, aside from maintaining an accurate historical record, it almost doesn’t matter if they had an unusual speaker arrangement for these shows or not. Maybe quadraphonic sound was too expensive for anyone but the Floyd to take on the road full time. Maybe the more powerful PAs and small effects clusters Paul mentioned were sufficient to capture the trippier soundscapes of Phish post-1994. Whatever the true story, it’s more significant that they were now a band making music appropriate for such complicated feats of audio engineering.