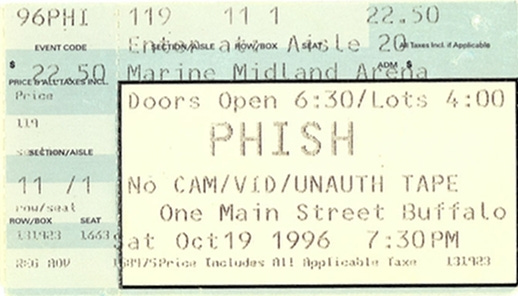

SET 1: My Friend, My Friend, Rift, Free, Esther > Llama, Gumbo, Down with Disease > Prince Caspian > Frankenstein

SET 2: AC/DC Bag, Sparkle > Slave to the Traffic Light, Bouncing Around the Room, Split Open and Melt, Fluffhead, Swept Away > Steep > Run Like an Antelope, Hello My Baby

ENCORE: Fee, Rocky Top

Well, we made it four shows into Fall 96, but I can’t resist any more: It’s time to address one of the cliched villains of this little-loved tour. It’s over there, nestled against Page’s array of keyboards, a Chekhov’s cowbell ready to go off in every single show so far and those yet to come. At some point in the night, the guitarist will flip his primary instrument onto his back and hop over to it, pull out some sticks, and spend the next few minutes doing what he thinks is best for his band. It’s the mini percussion kit, a divisive addition to Phish’s gear that, by 1996, was starting to overstay its welcome.

Trey added his new toy back in Summer 1995, and given its controversial reputation, I fully expected to write an entire post about it at some point during that year’s coverage. But to my surprise, it never really got under my skin, staying restricted to a handful of songs (Free, Simple, YEM) and usually accompanied by some delightful drone loops controlled by an auxiliary set of foot pedals. I finally filed my mild complaints in mid-November, but only as part of a four-pack airing of grievances.

At the time, I acknowledged that Trey’s intentions were pure, even if the results were repetitive and often unsatisfying. The mini-kit was an act of self-sacrifice to get other band members to step up, a nut Phish had never quite cracked due both to Trey’s instinctual aggression and the natural leading role of the guitarist in most rock bands. Its addition was the most directly observable evidence of the band’s mission in 95-96 to find a new, more democratic approach, the unlocking of which would facilitate 1997’s new heights.

But by the latter months of 1996, it’s clear that this experiment is not working. Every time Trey switches to the mini-kit in a jam in these first four shows — the Simple of 10/16, the Free of 10/17, the Suzy and YEM of 10/18, and Disease tonight — it leads to a near-identical outcome: a forced Page solo, a loss of momentum, and an improvisational dead end. Sometimes the band recovers, sometimes it doesn’t, but any post-percussion creativity is in spite of the mini-kit interlude, not a causal effect. On a tour where the band is very stingy with deep improvisation, it’s an extra bummer.

Tonight’s appearance is particularly egregious, as Trey dives into the Disease solo brilliantly, a mixture of chords and melodic lead that frolics over the song’s power anthem progression. It sounds like it will reclaim Disease’s excellent form from the summer, when it reasserted its jamming potential, but the gravitational pull of the mini-kit wins out. From 8:15 to 10:05 it’s just Page trying his best on various keyboards while Trey imitates a metronome, Mike very faintly alludes to the upcoming Halloween choice, and Fishman politely suffers the invasion of his turf. When Trey returns to guitar, he brings it to a fitting climax, but it would make a much better Type 1 version with those two mini-kit minutes snipped out, or maybe even something more if he had never wandered to his right.

It’s an unsparingly harsh illustration of the improvisational power dynamics in Phish circa 1996. Page and Mike’s strengths still lie in adding color and subtle nudges to the ideas originating from Trey; when given the spotlight, they’re not yet assertive enough to blaze new trails. On the percussion end, Fishman doesn’t need the help, and may even resent Trey’s offer — much of the drama of 1995 came from the two sparring on tempo, and here’s an even more intimate violation of his personal space. We’ll return to it later this year when more capable percussionists temporarily join the band, but I hardly ever think it works when Fish is forced to play with other drummers…his prodigious talents always sounds shackled, to my ears, even as recently as last month’s TAB shows.

Still, they just keep trying, and honestly, it makes sense, because it could have worked. New pieces of gear have often prompted leaps forward in Phish’s evolution, from Page’s grand piano in 1993, Trey’s digital delay loop in 1994, and Mike’s Modulus in 1997 to Page’s new synthesizer tones in 2017 and Trey’s new guitar in 2021. But they are also sometimes cul de sacs — the Marimba Lumina and Trey’s Echoplex pedal are recent examples, while Trey’s keyboard in 1999 falls somewhere in between inspiration and distraction.

The mini-kit was the latter, and a dead end, even if Trey had the right idea. The real breakthrough will happen in two weeks, when the band tackles Remain in Light and Trey realizes he can play percussion and share the foreground without even switching instruments. “On Remain in Light, every band member is playing drums,” Ryan “Trey’s Guitar Rig” Chiachiere said on a recap episode of HFPod this summer, and he’s exactly right. It’s a performance that will render the mini-kit unnecessary, even though it will live on undead for the rest of the tour, a well-meaning irritant.