There’s no more avoiding it, it’s time to talk about the bluegrass. Fall 1994 is incredibly well-regarded as a landmark in Phish history, but say anything about it online and you’re bound to hear some snark about the bluegrass sets, even, or perhaps especially, from the people who saw the tour firsthand. Even 25 years later, saltiness remains over the band’s acoustic setup intruding upon nearly every night of this 46-show run.

Phish had played bluegrass prior to 1994, of course. Rocky Top dates back to the ‘80s, their covers of Bill Monroe’s Uncle Pen and Josh White’s Paul and Silas debuted way back in 1990, Nellie Kane and Ginseng Sullivan joined the repertoire in 1993, and originals like Poor Heart, My Sweet One, and Scent of a Mule interpreted bluegrass through a Phishy lens. But Fall 1994 brought extra dedication to the genre, complete with a new, acoustic lineup — typically Trey on acoustic guitar, Mike on banjo, Fishman on washboard or mandolin, and Page on bass — and a fresh goofball cover of Boston’s “Foreplay/Long Time.”

After banjo player Steve Cooley’s guest appearance on 10/10, Phish brought Ginseng, Nellie Kane, and The Old Homeplace into this format, and some combination of those songs plus the Boston gag would appear in a mini-set at pretty much every Fall show thereafter. But when Rev. Jeff Mosier joined up for this mid-November Midwestern swing, the bluegrass fakebook really cracked open. Now, there were sometimes two separate bluegrass mini-sets interrupting sets or occupying the encore; one acoustic and one electric, or one with the good Reverend and one without.

Personally, I’m not that bothered by all the bluegrass. Sure, it gets a little repetitive when you’re following along with the entire tour, but as someone who also listened to every 1993 show in order, I much prefer the bluegrass set to the nightly Big Ball Jam and vacuum solo segment. I’m still amused by the Foreplay/Long Time cover, or at least amused by the reaction of crowds that remain largely unaware it’s coming even this deep into the tour (funny that it went into hiding when the legit bluegrass tutor showed up though…). It’s also easy to hear how hard they were working at it; their vocals and harmonies are as good as they ever sound in their career, and Mike’s banjo playing is a particularly charming detail.

That said, I’m more interested in why they chose to do this deep-dive into bluegrass at this particular point in their career. As I said yesterday, the stakes were pretty high for this tour — they were playing larger venues, recording each show for a live album, and pushing the improvisational boundaries harder than ever. Suddenly deciding to learn a bushel of Appalachian standards and play them on traditional instruments, most of them unrelated to their primary specialty, around a shared microphone...that’s a bold, even counterproductive move.

There are two prevailing theories as to why Phish suddenly went deeper into bluegrass in 1994. One is that it was a natural outgrowth of their earlier resolution to learn barbershop vocal harmony, which served as a kind of group voice-coaching exercise and also gave them a fun unamplified gimmick to trot out in venues with the acoustics to serve it. Adding some bluegrass songs, also unamplified on special occasions, expanded their options for this part of the typical Phish show. The other theory is that bluegrass has collective improvisation deep in its DNA, and studying its democractic processes with the added difficulty of learning an unfamiliar instrument could benefit the band’s communication skills on the rest of their material.

Perhaps you can make a case, with a liberal amount of hand-waving, that learning some old traditionals inspired the expansive, experimental Tweezers and Bowies of 1994; I’m skeptical. It also feels, to my amateur scholarship, like Phish never quite nailed this interweaving quality of well-played bluegrass. It’s often far too...polite, with a layer of irony keeping it at arm’s reach despite the band’s purest intentions — the mandolin player is wearing a dress, after all. Phish was always too irreverent and too ADD to be Americana, in the traditional sense. It reminds me of a great line from my pal Steven Hyden’s 2013 article on discovering Phish and figuring out what makes them different from the Grateful Dead:

The Dead set out to synthesize blues, country, folk, bluegrass, early rock and roll, and jazz into a psychedelic digest of 20th-century American music; Phish attempts something similar, only with the history of AOR.

The Dead, and Jerry Garcia most significantly, grew up on folk and bluegrass roots music in the mid-20th century. The members of Phish grew up in the 70s, and hard as they try, they can’t help but come to bluegrass filtered through two or three prior generations. It’s why they’ll always sound more convincing playing Led Zeppelin than Blind Willie Johnson...or Hot Rize instead of The Dillards.

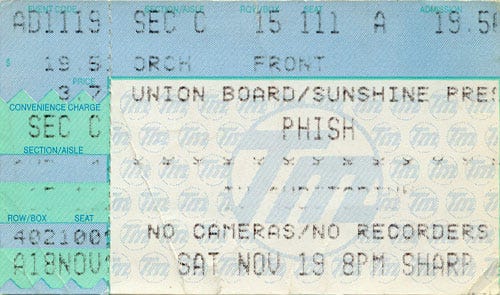

The best bluegrass set of the Rev. Jeff Mosier week throws these limitations into sharp relief. It comes on 11/19, but it’s not the Mosier sit-in at the end of the first set, or the solid Fixin’ To Die of the soundcheck. It’s what’s known to Phish fans as the “Parking Lot Jam,” an impromptu performance outside the band’s tour buses hours after the show proper had ended. The 12-song set includes the songs they’d been performing onstage but also several they had not officially debuted, and probably a few they were learning and playing for the first time on the spot.

It is incredibly loose and so much fun, with a fantastic, in-the-huddle recording that captures just how intimate and thrilling the moment must have been. The band swaps instruments even more than usual, Mosier steps up to play a more prominent role than that week’s deferential guest appearances, and some randos named Eric Merrill, Abe Stevens, and the mysterious "Jeremy" join in on instruments they presumably just brought along to the show, in case of emergency parking lot jam. You can hear the musicians teaching each other chords between or even mid-song, discussing what instruments they’re going to play (Trey gets a couple cracks at fiddle), and coming to each other’s rescue when someone forgets the words.

Beyond the music, the entire atmosphere is electric. A parking lot is no place for a shush battle: the whole crowd sings along to “The Old Home Place,” “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome,” and “Long Journey Home,” songs only just added to the Phish repertoire. Someone remembers playing “Mountain Dew” as a Boy Scout, a woman on somebody’s shoulders asks if she’s too heavy while another talks about smelling flowers (?), someone compliments Fish on tonight’s version of “Cracklin Rosie,” a voice requests Metallica, there are plenty of tone-deaf requests for decidedly non-bluegrass songs such as Curtis Loew, Ride Captain Ride, and Llama. You hear traffic passing by, and the set is brought to a close by a loud horn blast from the tour bus, likely from a driver ready to get his overnight shift started already, ya damn hippies.

In this chaotic hootenanny environment, you feel the spirit that’s been missing from the band’s official bluegrass attempts. “John Hardy” and “Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms” reach that locomotive, polyphonic choogle that’s inherent to great, brisk bluegrass, and the late-night versions of “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome” and “My Long Journey Home” have a more soulful desperation than usual. Instrumentally, it sounds less like the band is just taking turns taking solos, and more like the joyous conversational patter you get from a seasoned string band, jaw harp and all.

That Phish bluegrass works so well in such an unusual and logistically unsustainable format brings to mind a third, bittersweet reason why the band was so dedicated to the genre at this point in their career. Perhaps, subconsciously, the bluegrass set was a last-gasp pushback against losing the intimacy of small venues, an attempt to make the rapidly-swelling Phish experience feel cozy, like the old days, if only for a few songs. I commented yesterday on how spread out they appear on stage, separated by new gear and stretched out to accommodate bigger venues and crowds. Bluegrass, if nothing else, was an excuse to crowd back together in the middle of the stage around a single mic and make music staring into each other’s eyes.

So maybe the fact that they didn’t quite pull off the bluegrass set in Fall 1994, that it ended up instead irritating fans for decades to come, was a sign that it was too late, that the Phish scene had just grown too large for this strategy to work. Going forward they would have to create intimacy in less direct, more innovative ways — the flatbed truck jam and other secret festival sets, the ever-present, ever-growing inventory of inside jokes, or just by flying around the arena in a hot dog, as one does. The nostalgia baked into Phish’s bluegrass period isn’t just for an early 20th century songform, it’s for an earlier era of Phish itself, and like a whole lot of bluegrass songs say, there’s no going back.

[Stub from Golgi Project.]