At roughly 8:10 p.m. in Noblesville, Indiana, Deadheads breached the wooden fence behind the lawn at the Deer Creek Music Center, pouring into the venue as Bob Weir sang “Desolation Row.” “Check out the back wall,” deadpans Phil Lesh on the band’s closed-circuit monitors, as the crowd cheers the intrusion, pouring thousands of ticketless fans into a sold-out venue. Tension was already high that night — Jerry Garcia had received death threats before the show, causing extra security to surveil from the pavilion rafters — but the band decides it’s safer to keep playing, albeit with the house lights on for the entire second set. “There’s a riot going on outside, there’s no need to drag this on,” Mickey Hart says as “Space” winds down. “Let’s get out of here.”

The next morning, the Dead cancelled their second night at Deer Creek and left early for their tour’s penultimate stop in St. Louis. In a letter to the fans on July 5th, Dead publicist Dennis McNally minced no words. “Your justly-renowned tolerance and compassion have set you up to be used,” he wrote in a message signed by all six members of the band. “This is first a music concert, not a free-for-all party...We're all supposed to be about higher consciousness, not drunken stupidity.”

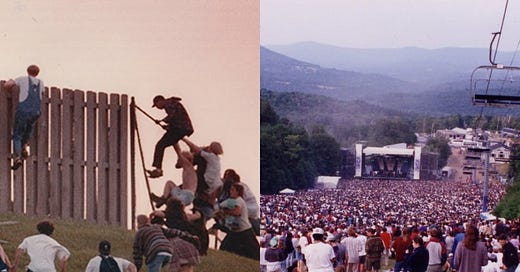

850 miles northeast in Vermont, Phish is on setbreak when the Deer Creek fences fall. Their concert that night had experienced its own crowd control issues, with thousands of ticketless fans descending upon the Sugarbush Ski Resort and sneaking past a thin line of security. “By showtime it was clear that thousands upon thousands of ticketless fans had made their way to Sugarbush, to the parking lot, and up the ski hill which formed the makeshift amphitheater,” the Pharmer’s Almanac remembered. “In fact, fans were pouring over the flimsy barriers which flanked the viewing area. A few guards tried to stop the first fence-hoppers, but when a sea of people oozed in from every side, venue security just gave up.”

An estimated 7,000 extra attendees joined the “official” capacity crowd of 12,500 — but since it was just a stage set up at the bottom of a big mountain, nobody seemed to really mind. Before the last song of the first set, Trey lightly reprimanded the freeloaders, reminding them that the show was supposed to be a benefit for the King Street Youth Center in Burlington: “For those of you who happened to be wandering through the woods and kind of found yourself at the concert, maybe you could take the money you would’ve used to buy a ticket and donate it.”

It’s hard to imagine a more apt moment where the jamband baton was passed from the Grateful Dead to Phish, for better or worse. Jerry Garcia still had four shows left to play and a month and change to live, but in 1995, a multitude of forces, including nature itself, appeared to be telling the Dead it was time to pack it up. Earlier in the tour, lightning struck 3 fans outside of RFK Stadium; a few days after the Deer Creek incident, a storm caused a porch collapse at a campground near the Riverport Amphitheater, injuring a hundred Deadheads. The very first show of the tour, 75 miles north of Sugarbush in Highgate, VT, had itself been crashed by thousands of ticketless fans. Paired with Jerry’s obvious ill health, these events were accurate omens that the end was near.

But as the Dead limped across the country on the “tour from hell,” Phish enjoyed the cover it provided. Aside from the debacle in Waterloo — exacerbated by the Dead’s tour being nearby and on a day off — their own summer jaunt had been largely incident-free, especially compared to tense moments in the previous fall when small towns were terrorized by Phish fans (e.g. tailgating in faculty parking spots). Moving up to the amphitheater circuit meant a lot of undersold shows, but until the final week, no nights where more people showed up than the venue could handle.

I think it’s pretty obvious that Phish enjoyed being ever so slightly out of the spotlight. With the immense gravity of the 90s Dead attracting the hippie hanger-on community, Phish was free to build a fanbase on its own terms, at its own pace, without the logistical headaches of managing a traveling parking-lot circus. And being America’s #2 Jamband allowed them to experiment freely, a license which they have wholeheartedly embraced this summer, no matter what you think of the results. That more free-spirited approach may have helped them organically poach Dead fans who were growing disenchanted with their favorite band’s predictability and low energy, two needs Phish could certainly satisfy in this era.

Their simultaneous co-existence also meant that Phish, to this point, never felt like they had to be a replacement for or a competitor with the Dead, just a complementary flavor. The musical influence of the Dead on Phish was and is perpetually overstated; Phish drew more from the general improvisational rock show format established by the Dead than they did from the Dead’s actual sound. But it’s an interesting thought experiment: if Jerry Garcia had died in 1993 instead of 1995, thrusting Phish into the “heirs to the Dead” role two years earlier, would the rest of their miraculous 90s evolution have played out the same way?

In a grim sense, Jerry’s death and the dissolution of the Dead came at the perfect time for Phish. By the time the Deadhead bandwagon had shifted to Phish — which started to happen in Fall 95, but really poured in the following summer — they had already built up confidence in their own approach, had ridden it to all the same non-stadium venues as the Dead, and as such didn’t feel a need to make concessions for the new influx. Throwing the occasional Bertha or St. Stephen into their set would’ve been the easiest move possible to light up those new fans (and many of the old ones too), but it wasn’t obligatory by this point, and they wisely opted against it.

Instead, Sugarbush pointed the way forward. The Dead famously hated playing stadiums, but felt forced into it to meet ticket demand — part of the issue at Deer Creek was that 50,000 fans showed up to a 24,000-capacity venue. Phish’s homecoming run at Sugarbush, on the other hand, was designed as a destination event for their biggest fans, building off last year’s triumphant tour closer with on-site camping, a makeshift stage, and, it appears, loose security. The organization might not have expected nearly twice as many fans as tickets sold, but their unorthodox choice of venue was elastic enough to accommodate it.

Musically, that relaxed environment gave them the freedom to be as weird as they wanted, tonight playing the tour’s second Double Nancy of I Didn’t Know and Halley’s Comet, busting out a song (Camel Walk) they hadn’t played since The Front days, and pulling an inside joke with the tour’s shortest Tweezer directly into Ha Ha Ha. Fans wandered up the mountain, far from the stage, where the sound was supposedly better, and made makeshift campsites throughout the wooded resort, whose ownership let them be. As the Pharmer’s Almanac summarized the whole two-day experience, “It was Phish summer camp. The realization of a dream.”

Summer camp worked out so well that they’d take it to the next level in 1996. If tens of thousands of Phish fans wanted to celebrate the end of the tour with them in a remote area, what if, instead of renting out a football stadium or a ski resort, Phish built their own temporary civilization somewhere in the Northeast, with enough room to welcome everybody who wanted to come? The Clifford Ball and its descendants became possibly the most meaningful achievement Phish pulled off that the Dead never could, utopias of music and fan community that only spoiled when Phish encountered their own tour from hell. On the very same night that one world expired in a cloud of tear gas, another world, spending a little time on a mountain, got ready to carry that load.

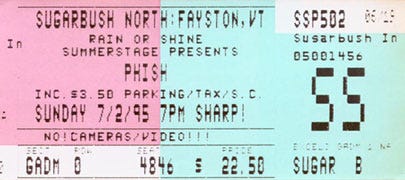

[Ticket stub from Golgi Project.]

Great reflections on a powerful intersection in the music-space-time continuum.