Found Objects

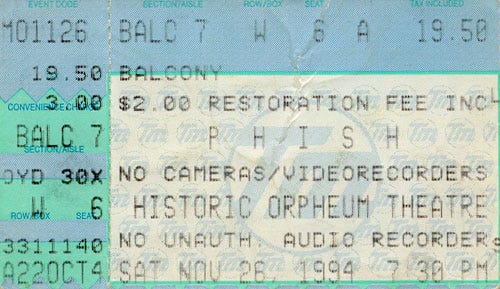

11/26/94, Minneapolis, MN, Orpheum Theatre

Because he’s forced to live with me, my older son has heard Phish almost every day of his eight years of life. And apparently, this prolonged exposure prompted a neural adaptation where he can block out any and all Phish-related frequencies at will. I reached this conclusion last weekend, when we were listening to the 11/25/94 Purple Rain and he turned to me, eyes wide with alarm, and asked “What. Is. That. Sound?”

“Oh that? The drummer plays the vacuum!” I said, pouncing upon a rare moment of Phish interest and quickly calling up some photos on my computer.

“Uhhhhh, okay,” he said, rolling his eyes, and turning back to his Legos.

For Phish’s first decade, Fishman’s vacuum was the very definition of a novelty, a conversation piece. I wouldn’t be surprised if they sold more than a few tickets in the early days solely on the back of some “Dude, you wouldn’t believe it, a guy in a dress sucks on a vacuum!!!” word of mouth. Up through 1993, the band seemed to feel an obligation to satisfy this subset of their audience, with a Fish segment showing up to derail the second set of almost every show. Thankfully, 1994 finally shifts away from that nightly requirement, only giving Fishman center stage every few shows and preserving its welcome.

But the more intriguing development is that Fish’s vacuum is occasionally freed from its primary occupation of providing the solos in his repertoire of Syd Barrett, Prince, and Wizard of Oz covers. When NO2 made its perplexing flurry of appearances in Summer 1994, Fish rolled out the Electrolux to provide some additional sound effects for Mike’s dental narrative. On Halloween, he used it to Phishify “Revolution 9,” providing flatulence between spoken-word readings of the original’s samples. These vacuum deployments aren’t exactly serious, but they did suggest that the “instrument” had some interesting sonic potential beyond the usual gag.

That promise finally delivers in the middle of this show’s epic David Bowie, the longest performance of the song ever, and quite possibly the band’s longest jam to this point — a record it would hold for approximately 48 hours. What’s startling about this 36-½ minute Bowie is that it is business-as-usual for about half the runtime, during which it’s recognizably a Bowie jam, not spiraling off into free improv like most other Fall 94 mammoths. There’s even a point, right around the 18-minute mark, where they almost drop into the song’s conclusion. But like so much of this tour, when faced with that choice, they take the hard way out.

What follows is several remarkable, drum-less minutes, a Page/Trey conversation that is eventually joined by Fish’s vacuum in a much more subdued and atmospheric role. Here, it sounds more like a breathy Theremin than a whoopie cushion, a howling wind that inspires further found-object weirdness. First, Mike brings out his one-string bass and makes some “cartoon character using an awning as a trampoline” noises, then Trey does his megaphone siren Doppler effect trick, and Page...just stays on piano, which is fine, someone’s gotta mind the store. It’s Phish as noise act, rummaging through their toy box and using items that only barely qualify as instruments to make something closer to sound art than what most would call music.

Eight minutes later, Fish wanders back to the drum kit, and what follows is ten of the best minutes you’ll hear in Fall 94, a truly unique and wonderful stretch of improv. It flirts with Simple, Guyute, and Weekapaug, but is mostly driven by some fascinating Trey/Fish push-and-pull that foreshadows the style of 95, with Trey playing some uncharacteristically Tuareg-style lines (not for nothing did I compare it on Twitter to the Gunn-Truscinski Duo). Then, in true Phish fashion, the band totally blows the dismount, which, even more than its length, might have disqualified it from A Live One contention. Alas.

But getting back to that strange middle section, it’s hard to imagine the final third hitting so hard without being preceded by an avant-garde diversion. It’s more than just the new tension/release effect I described two shows back, it’s like a sonic palette cleanser, a very extreme exercise to get them off their primary instruments and break familiar habits. And it’s a practice that will continue to crop up in Phish history; we’re getting close to the Trey percussion kit era, Page will eventually get a real Theremin to tinker with instead of Fish’s appliance imitation, and in more recent years, there’s the Marimba Lumina and Mike’s drill.

In these early stages, when Trey and Mike’s rigs were still relatively simple and Page largely stuck to piano and organ, anything at hand that could add some new sonic flavors was particularly important. Repurposing Fishman’s vacuum was an inspired choice, so long as it was used sparingly; and it was, only turning up a handful of times in “serious” jams thereafter (most notably, 12/30/97 and 10/31/98). It’s a fun paradox: sometimes the deepest, darkest Phish jams required the dumbest, goofiest Phish bit.

[Stub from Golgi Project.]