There are those who would say that the song of Summer 95 was David Bowie, and others who would argue for Tweezer, or a representative from the new batch of songs that would go on to form the core of Billy Breathes. But in terms of frequency, all of these songs sit in the shadow of four men on stools, strumming acoustic guitars. Acoustic Army was the most-played song of the tour, played 12 times in 22 shows — more than Taste (10), Theme (9), or Free (7). It would remain at a fairly high frequency in the fall/winter, appearing in 15 of 54 shows, before vanishing entirely after 12/8, the rare case of a heavily-played Phish song entirely confined to a single calendar year.

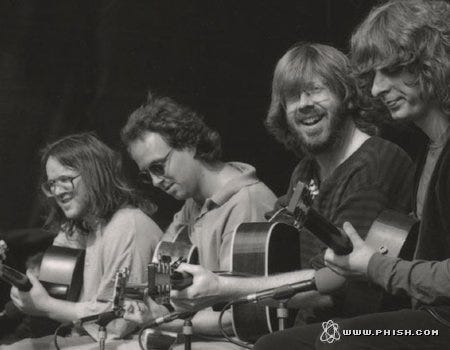

Furthermore, Acoustic Army often turned up near pivotal moments of Summer 95 shows, in its usual late second set slot. It’s the first song played after both the Mud Island and Finger Lakes Tweezers, it chases hearty versions of You Enjoy Myself at Deer Creek and Jones Beach, and tonight, in the first of two shows at The Mann, it follows up a very pretty Harry Hood. After the sensory overload of these massive jams, Phish veers to the other extreme: a mellow, sometimes barely audible instrumental piece for four guitars, played nearly shoulder-to-shoulder at center stage.

On a tour that is mostly maximalist, Acoustic Army is counterintuitive. But it has clear roots in older Phish provocations, most obviously the barbershop songs, but also the bluegrass mini-sets of 1994, Fishman’s very occasional solo performances of his composition Faht (basically a visual gag, Man in Dress Plays Folk Guitar), or even farther back to “And So To Bed” from The White Tape. It combines a lot of the band’s favorite gags: playing very quietly in very large venues, forcing a partying crowd to listen closely, and even deploying a false ending to expose the noobs who cheer too early.

Like the unamplified performances of years past, it’s a test that most audiences fail. But Philly does itself proud:

“I just do want to say, on this whole tour, that acoustic thing we just did, you guys, it was a great audience, you got really quiet, it really helps. Thank you, thanks.” - Trey, between The Mann Acoustic Army and Sweet Adeline, which they sang in surgical masks because the timestream is crumbling.

But there are more interesting dimensions of Acoustic Army that make it an appropriate song for this point in Phish history. For starters, there’s the song itself, a far more calm and ruminative composition than the band typically played. Compare it to the bluegrass songs they cover, all of which are played at breakneck speed whether on electric or acoustic. Acoustic Army, by contrast, moves at a snail’s pace, a gentle hike through the woods instead of a runaway horse buggy.

It’s got a bit of Led Zeppelin III in it, or the soft, hushed songs that close out the first disc of The White Album; not for nothing that they followed Acoustic Army with Good Times Bad Times or While My Guitar Gently Weeps on several occasions. It’s also got a sort of communal guitar soli vibe, eight hands combining to simulate the textured finger-picking of a John Fahey or Leo Kottke. The limited skills of Page and Fishman on guitar — in the Deer Creek video, you could see how their left hands barely budge for the duration of the song — gives the song a steady background drone like a raga, while Trey and Mike softly weave the melody on top. It’s a hypnotic effect, and sets up the listener for a (gentle) jolt when they suddenly switch to unison chords, punctuated with a harmonic (and all four of them wave their guitar necks in sync, because they’re dorks).

That eight-handedness also reflects the band’s increased emphasis in 1995 on democracy and performing as a single unit, not a frontman and his accompanists. As I said on the song’s debut, Acoustic Army is another case of the band using explicit constraints to equal out their contributions; instead of Trey trading his guitar for a percussion kit, it’s everyone else trading their instruments for a guitar. Trey, of course, still handles lead duties in the song, but it’s composed and mixed to be a cohesive fabric, with no part more important than the rest. There’s no improvisation to Acoustic Army, but it’s still the kind of exercise that would train each member’s ear to hear the other three’s contributions as loudly as their own.

Acoustic Army is just the first formalist step in this direction; later in 1995, it will be joined by Keyboard Cavalry (aka Keyboard Kavalry aka Keyboard Army), with all four members playing a piece of Page’s rig. Fall 1995 will also bring the first phish.net-official “Rotation Jam” of four total in the mid-90s, when the band trades places with, er, variable results. Still later comes Walfredo and Rock A William, songs (in the loosest sense) written for some of those alternative configurations. Finally, they’ll discover that the funk genre can have the same equalizing effect with much more palatable sounds, and the experiment takes off from there.

There’s a third angle to Acoustic Army that I hadn’t considered until the Deer Creek Dinner and a Movie and its concurrent Twitter discussion. After jamband provocateur Thoughts on the Dead called out Phish for the rock band cliche of acoustic-song-on-stools, he and Jesse Jarnow engaged in some light banter about the sincerity of the song and setup. Having previously encountered only the audio, it honestly had never occurred to me that Acoustic Army was anything but earnest, especially given that its winking, alliterative name was supposedly bestowed by the fans, not Phish themselves.

But the video footage and their slightly hammy demeanor made me wonder if the song really was a satire of rock tropes, as much a piss-take as the acapella Freebird or putting a vacuum solo in Purple Rain. One could argue that Summer 95 subverted arena rock on two fronts: through tongue-in-cheek gimmicks like Acoustic Army and by playing half-hour, often uncomfortable improvisations almost every night instead of “the hits.” Through that lens, Acoustic Army deserves to be in the “song of the summer” conversation, as an early example of Phish playacting arena rock before they could no longer tell where the joke ended and truth began.

[Stub from Golgi Project.]