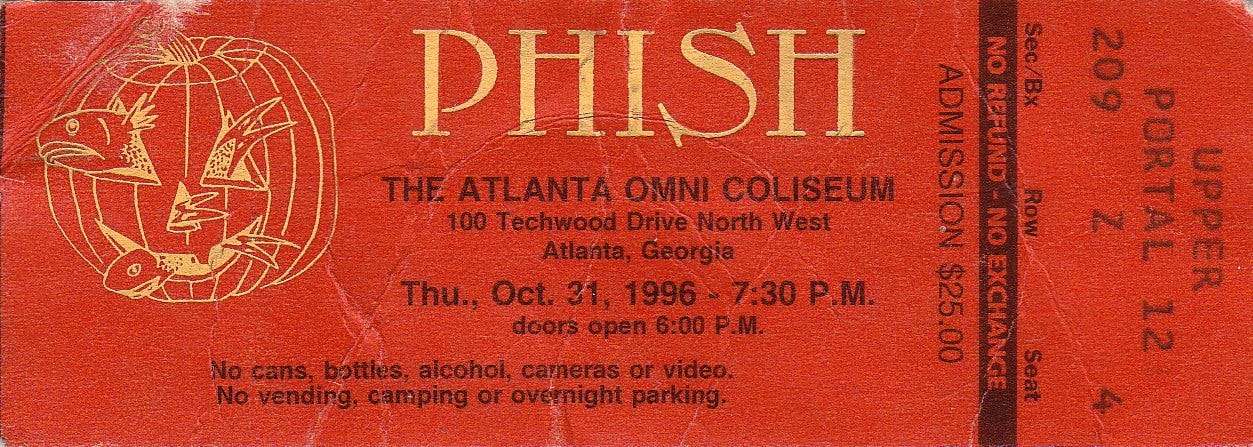

SET 1: Sanity > Highway to Hell > Down with Disease > You Enjoy Myself, Prince Caspian > Reba, Colonel Forbin's Ascent > Fly Famous Mockingbird > Character Zero, The Star Spangled Banner

SET 2: Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On) > Crosseyed and Painless, The Great Curve, Once in a Lifetime > Houses in Motion -> Seen and Not Seen -> Listening Wind > The Overload

SET 3: Brother, Also Sprach Zarathustra > Maze, Simple -> Swept Away > Steep > Jesus Just Left Chicago > Suzy Greenberg

ENCORE: Frankenstein

I. What Is A Band?

Every band, no matter how hard it tries to be an equal democracy, has a leader. It’s a social phenomenon that goes much deeper than music, or even humanity; packs of wild animals conduct a ceaseless battle for dominance over the highest stakes of reproduction and survival. Very rarely, a group can be commanded by an alliance of two leaders: your exception to the rule Jagger/Richards situation. But more often than not, there’s an alpha (usually) male, and any threats to their supremacy, even with the best of intentions, produces friction and, eventually, destruction. Yet, in some rare and special cases, that tension also produces a creative and combustible magic.

Phish, from the very beginning, made all the right noise about being a band of equals. But Trey Anastasio was quite obviously the head of state — he wrote and sang almost all of the songs, crafted the band’s setlists, did most of the talking onstage, conducted the band as his orchestra interpreting his vision of a rock band with equal comfort in sophisticated composition and open improvisation. Trey is the most benevolent dictator possible, always eager to share the spotlight and credit with his bandmates. But there’s no debate over who called the shots for Phish from 1983 until today, and who holds the ultimate veto power.

For Phish’s first phase, this hierarchy worked out just fine. I’m not aware of any band drama over their first fifteen years or so, apart from the very early departure of Jeff Holdsworth, and even that seemed like a him problem, not a them problem. With their success steadily growing, the path of least resistance would have been the status quo, keeping Trey alone at the helm, following the same trajectory that assembled a cult of personality around Jerry Garcia.

Phish didn’t want to do that. Not out of some Behind The Music clash of egos, but out of their relentless creative drive to always chase the new, not settle for the old. Their desire to flatten out the band’s power structure started poking through in the exquisite corpse jams of 1994 and the full-band songwriting of 1995. Trey tried to shift his style away from that of the stereotypical lead guitarist, trying more textural playing and even giving up the guitar altogether for stretches of jams, leaving space for another member to step up. But 1995, for all its achievements, still revolved around Trey (and to a lesser extent, Fish), who couldn’t resist playing the guitar god — perhaps with tongue somewhat in cheek — as the band grew into its new arena rock status.

1996 was a crossroads. Phish could carry on as they always had, with Trey not quite a frontman, but also not quite a band of true equals. Or they could keep hammering away at a more communal approach, even if it wasn’t yet working. Their indecisiveness and frustration left the year feeling unusually flat, an unwelcome interruption to the asymptotic path of the decade so far. If the democratization of Phish was going to work, they needed to find the secret formula fast; the alternative was stasis, at best, and dissolution, at worst.

II. Hi, I’ve Got A Tape I Want To Play

1980 was a crossroads. Talking Heads were a bunch of art school dorks who got improbably swept up in the dawn of New York City punk, squares playing jittery songs with autistic spectrum lyrics alongside angry junkies and taboo-violating weirdos. Hooking up with visionary producer Brian Eno, they were already inventing post-punk before punk ended, earning critical accolades but little in the way of commercial success beyond the Son-of-Sam novelty of “Psycho Killer” and a clever Al Green cover. Increasingly, the Talking Heads were seen as a vehicle for frontman David Byrne, the charismatic eccentric who some speculated might do better as a solo artist.

On Remain in Light, Talking Heads pushed against this narrative. Instead of Byrne coming to the studio with pre-written songs, they went to the Bahamas and simply jammed as a band with no preset compositions, drawing from the African sounds they were all independently exploring. The idea, inspired as well by the dawn of hip-hop, was to create “loops played live,” source material that could later be assembled into more traditional songs by Byrne and Eno, a more commercial slant on what the duo were experimenting with in parallel on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. As told to Jon Pareles in 1982:

The ideal, as Byrne put it, was that "in sacrificing our egos for mutual cooperation, we got something - dare I say it? - spiritual... This kind of spirituality is joyous and ecstatic and yet it's serious." A utopian paradigm.

The legalities were controversial — compositions were later credited to “David Byrne, Brian Eno, and Talking Heads,” to the irritation of drummer Chris Frantz and bassist Tina Weymouth — and the process did little to break the momentum of Byrne’s auteurship walling him off from Talking Heads. But the results were magnificent, a post-punk milestone and a perennial greatest-album-of-all-time-list resident. It’s the rare departure project that both succeeded in its artistic intent and produced a hit: “Once in a Lifetime,” a worthy contender for the defining Talking Heads song. The subsequent Speaking in Tongues and Stop Making Sense may have been the high water mark for the Heads’ commercial success, but Remain in Light remains their masterpiece.

Forty-one years later, it’s still an astonishing album, and the quality that leaps out of the speakers is how selfless it is. Every track is a machine constructed from microscopic instrumental gears: itchy guitar, horn stabs, cyclical bass, cut-up text, percussion hits, synthesizer squiggles. It’s Borg-like; there’s no telling where the individual ends and the collective begins. But like everything in nature, the album is also subject to entropy — its groove gets slower and slower, looser and looser, until it divides and dissolves into pure noise.

III. One Step Ahead of Yourself

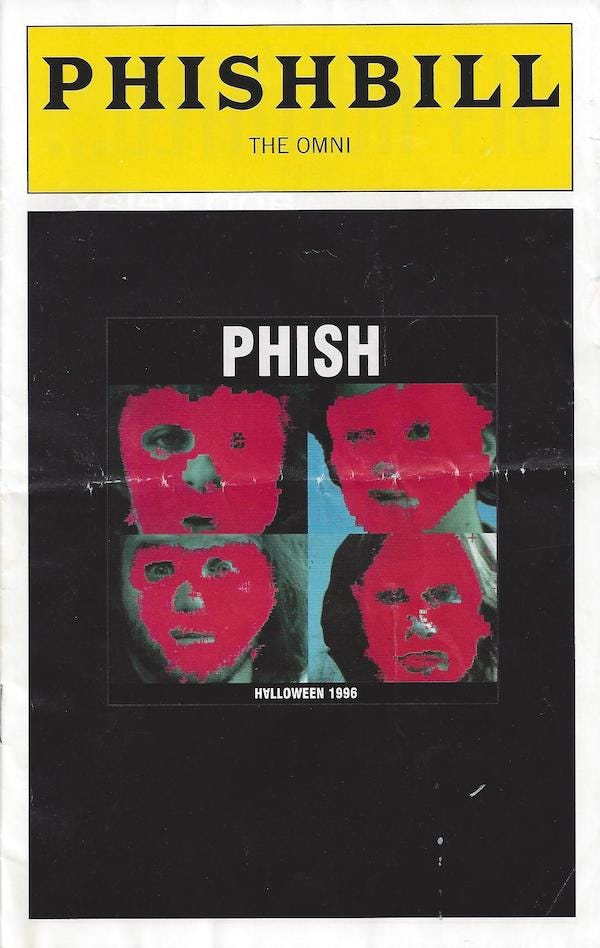

Officially, Remain in Light was the first album Phish chose for themselves to play on Halloween. There have always been rumors that they put their collective thumb on the scale in 1994 and 1995 and didn’t take the true top vote-getter, but 1996 didn’t bother with that democratic illusion. The band picked what they wanted to play, and via the first Phishbill, they told you what it was when you came in the door. The album was their opportunity to make a proactive statement with the Halloween tradition, instead of providing reactive fan service.

Phish chose a record that came out when they were all in their mid-to-late teens, not a baby boomer hand-me-down. At the pliable age of high school, they were college radio fans, and the early Phish cover catalog reflects that time and genre: XTC, solo Lou Reed, Robert Palmer…and a Talking Heads song that’s not on Remain in Light. While their fakebook would eventually be majority classic rock, that’s not necessarily the music they were brought up on, or that was most formative to their approach. Talking Heads are not quite peers, not quite ancestors…sort of cool older siblings.

“I may have listened more to this album than any other album, ever,” Trey says in the Phishbill. “I practically learned how to play guitar by listening to Remain in Light. When I wanted to practice something new, I would put the album on and jam along. This was literally my guitar-practicing album; it was so much more fun than playing over a metronome.”

The enthusiasm that Phish has for this album can be heard in the first set, where they sound like they can’t wait to dig into the cover — YEM and Reba are set at tempos almost too fast for them to play. With no Karl Perazzo onstage yet, they run through some of their weirdest material: Sanity, Highway to Hell, and a Forbin’s > Mockingbird with David Byrne cast as a mountain-sized god. Previous Halloween first sets may have contained some important messaging; tonight’s is all about getting to the main course as quickly as possible.

All that enthusiasm pays off in the second set, the only Halloween cover costume that feels like Phish has truly disappeared into the role instead of just playing a recital. The band was up late the night before cramming; according to Trey in The Phish Book, they hadn’t actually played the album all the way through until the soundcheck on Halloween. But it all clicks in front of the audience, Phish + 3 lost in the hypnosis of building an ecstatic groove from small, interconnecting parts. “I was out of my body during the set, overjoyed,” Trey says.

They’re out of their comfort zone and loving it. Trey is finally free to play rhythm guitar for an extended period, except when he’s called up on to recreate Adrian Belew’s deranged guitar and synth-guitar solos, unleashing every guitar pedal trick he’s learned over the last two years and sounding totally unlike himself. Mike is forced into playing repeating lines instead of wandering Lesh-style between rhythm and melody. Page leans on synthesizer and clavinet tones more than ever before. Fishman describes the experience as “Drumming and Singing at the Same Time 101,” and it’s low-key the band’s best vocal performance possibly ever (one of the things they tell David Byrne in 1998 is that it got them all singing more, using “vocals as percussion instruments”). Perazzo’s percussion is essential, but the guest horns also kill it, particularly Gary Gazaway’s replication of Jon Hassell’s echo-dripping trumpet sound.

It’s foolish to think that Phish improved up on the original LP, but instead of rote mimicry, they created a new, parallel version that excels on its own terms. The Talking Heads own live performances, as heard on The Name of This Band is Talking Heads or the famous 1980 Rome bootleg, focused on the first five songs, played out of order and also rendered somewhat more sinister than on the record. It’s not an obvious album to play front-to-back live, with its descending BPM and a last third that is heavy on atmosphere, nearly spoken word.

Phish not only tastefully extended some of the songs but also organized them into more of a continuous suite; there’s really only one pause, before “Once In A Lifetime.” The first half is played even faster than the Heads’ versions — closer to the sweaty delirium of Stop Making Sense than the darker Rome ‘80. They also spruced up the darkness of side B with some conceptual hijinks, putting Mike in an easy chair (and Trey on bass!) for “Seen and Not Seen,” turning “The Overload” into live musique concrete meets Einstürzende Neubauten with the help of crew members on power tools. It’s the most relistenable Phish Halloween cover by a country mile.

IV. Some of You People Just About Missed It

And by many reports, the Atlanta crowd…wasn’t feeling it. Remain in Light wasn’t exactly obscure in 1996, but it’s definitely a less universal favorite than “The White Album” or Quadrophenia; there’s one big cheer during the set, a “finally one we’ve heard before” sigh of relief when “Once In A Lifetime” begins. Looking back from 2021, when Talking Heads are a no-brainer member of the official jamband canon, it’s an unlikely flop. But in the mid-90s, the sliding timeline of classic rock hadn’t quite reached the early-80s prime of the Heads, the critical consensus hadn’t yet reappraised them as one of the Great American Bands, and they were a foreign entity to the very insular tastes of the common jamband fan.

But for the members of Phish, it was a logical fit right away:

“It made sense that we did Remain in Light right before a year in which we concentrated on sparser grooving jams, various synth textures, and cascading delayed cycles on top of it,” Mike observes in The Phish Book. “Remain in Light probably stuck with us more in the short run than either of the other two Halloween albums.”

“What I like about Remain in Light, besides the lyrics, which are incredible, is the textural aspect,” Trey in the Phishbill again. “I like music that’s got an African influence, where nobody’s soloing but everybody’s playing these tiny patterns and leaving a lot of space. It’s something we try to do with Phish, a process where everyone is adding bits and pieces - sort of like creating a mosaic of sound.”

Despite the common wisdom that Hallowen 96 directly begat the cowfunk sound of 1997, Phish’s reinvented sound doesn’t sound all that much like Remain in Light, frequent Crosseyed teases notwithstanding. The minimal 1997 groove is much more akin to The Meters than the Americanized afrobeat of Remain in Light; without the horns and supplementary percussion, it wasn’t really a vibe that Phish on their own could recapture. But the album’s philosophy, a danceable ego death assembled from interlocking parts like a finely-made watch, was exactly what Phish had been chasing for the last two years, if not over a decade of hey-hole exercises and all-night psychedelic marathons.

Halloween ‘96 proved to Phish that they could do that, but also that it was going to take a much deeper makeover than they’d ever attempted before. The Phish catalog of originals wasn’t really set up for this kind of groove-based playing; you’re not going to be able to apply the lessons of “The Great Curve” to, say, “Horn” or “Lizards.” Tellingly, the third set of 10/31/96 doesn’t really carry over any of the themes of the cover set, despite Perazzo’s presence — only the last couple minutes of Simple sound of a piece with the musical triumph they had just achieved.

Translating the ethos of Remain in Light into their own language was going to require new material (Story of The Ghost was largely written and recorded using the same procedure), the temporary shelving of old favorites, and a gamble that Phish fans would go along for the ride after mostly scratching their heads on Halloween. It also meant attempting a disruption of that natural order of bands, a true leader-less structure, a near impossible balance that the Talking Heads couldn’t even maintain for the entire recording of Remain in Light, never mind afterwards. To make the 1996 Halloween costume a guidepost instead of an anomaly, Phish would have to do what many bands tried and failed: to become a true foursome, a parliament of equals, a selfless tapestry.

“This album embodies a concept that’s become more and more important to us,” concludes Trey in the Phishbill, “that a group, playing as a group and not as four individuals can go so much further. It’s important to learn to play in a context where every note counts and the band is linked together as a whole.”

There was definitely a lot of people there that were not familiar with the Talking Heads and the back half of the album is pretty odd. It was also probably the most collectively stoned crowd and I've ever been in. I don't think I breathed during Trey's solo on Great Curve. Still to this day the most impressive solo I ever saw him play in person.

You’re a great writer , thanks for doing the Lord’s work.